Asynchronous Tasks with std::async

Offload heavy work to other CPU cores. Learn how std::async and std::future enable concurrent execution.

So far, we've generally considered basic functions as the unit of work in our designs:

void ProcessData() {

DoWork();

}This line of code transfers control of our execution over to the DoWork() function body, and we get control back once DoWork() returns.

There is another way we can set this up. The <future> header lets us declare asyncronous units of work using std::async, and we then wait for it to complete using the wait() method.

Our previous DoWork() example could be written like this:

#include <future> // for std::async

void ProcessData() {

auto task = std::async(DoWork);

task.wait();

}Why would we prefer this approach over the simple DoWork() expression? The key benefit is that we can do other work whilst we wait for our task to complete.

Below, our Sequential() function performs TaskA() and then TaskB(), whilst our Concurrent() function can do both tasks at the same time:

void Sequential() {

TaskA();

TaskB();

// Both tasks are now complete

// ...

}

void Concurrent() {

auto task = std::async(TaskA);

TaskB();

task.wait();

// Both tasks are now complete

// ...

}If each of our tasks require 200ms of CPU time, Sequential() will take 400ms to complete, whilst Concurrent() will do the same work in approximately 200ms.

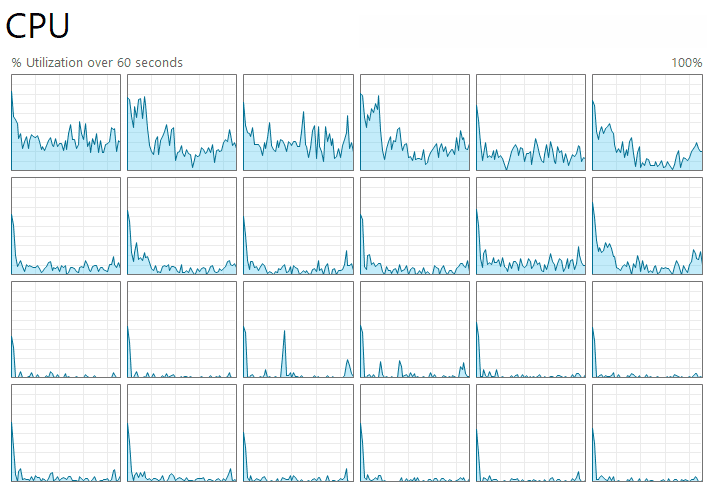

As you may have guessed, the magic that makes this happen is multithreading. Our CPU has multiple cores. Our Sequential() example is using only one of them, whilst Concurrent() is using two:

We'll talk more about multithreading soon, but let's briefly cover what std::async() returns.

The std::future Type

The std::async() function doesn't return the result of the asynchronous operation directly. Instead, it returns a std::future object. Think of std::future as a promise or a handle to a result that will be available at some point in the future.

It's a placeholder object that will eventually hold the return value (or an exception) from the task we provided to std::async():

// DoHeavyWork() returns nothing / void

// So std::async(DoHeavyWork) returns a std::future<void>

std::future<void> task1 = std::async(DoHeavyWork);

// GetHeavyString() returns a std::string

std::future<std::string> task2 = std::async(GetHeavyString);This separation allows the calling thread to continue doing other work immediately after launching the asynchronous task, rather than waiting for the result.

The std::future object gives the calling function a way to check on the status of the asynchronous task, wait for it to complete, and retrieve its result when it's ready.

Blocking

When a function is waiting on another function to complete, the waiting function is sometimes described as being blocked. With a regular function call, the caller is blocked until the function it called completes:

void FunctionA() {

// A blocking invocation - execution of FunctionA

// is blocked until FunctionB returns

FunctionB();

// Function B is complete and I can now proceed

}If FunctionB is instead launched as an asyncronous task, FunctionA is blocked from the moment it calls wait() until the task is complete:

void FunctionA() {

// A non-blocking invocation

std::future<void> task = std::async(FunctionB);

// I am not blocked by FunctionB. I can do more work here, but

// I should be aware that FunctionB is probably still running

DoMoreWork();

// If I want to ensure that FunctionB is complete, before I

// proceed, I should call wait

// Calling wait() will block me until FunctionB completes

task.wait();

// FunctionB is complete and I can now proceed

}Excessive blocking can sometimes represent an inefficiency, however, some blocking is also a necessary part of multithreaded design.

Blocking execution using wait() is how we ensure a task is complete before we proceed to a part of the program that requires that task to be complete:

It is safe to call wait() on a std::future that is already complete. In that situation, wait() will immediately return control and let us proceed.

Getting the Result

If the asynchronous task returns a value, you can retrieve it using the get() method. Calling get() on a std::future object will:

- Block the calling thread if the asynchronous task has not yet completed, just like

.wait()does. - Return the result of the task at the end of the block.

- Throw any exception that the asynchronous task might have thrown.

It's important to note that wait() can be called multiple times on a std::future, but get() can only be called once. Subsequent get() calls will result in undefined behavior. If you need to access the result multiple times, you should store it in a local variable after the first call.

Below, our Sort() function starts an asyncronous task to sort the array provided as an argument. When it is complete, it returns a std::string with a success message:

#include <vector>

#include <future>

#include <thread>

#include <chrono>

#include <algorithm>

#include <string>

struct Player {

int score;

};

std::future<std::string> Sort(std::vector<Player>& players) {

return std::async([&players](){

std::ranges::sort(players, {}, &Player::score);

return std::string("Sort complete");

});

}

void ProcessAndGetResult() {

std::vector<Player> players(1000);

// Launch the task

std::future<std::string> asyncResult = Sort(players);

// Simulating other work...

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(50));

// Wait until the task is finished, and get the result

// If the task isn't done yet, this line blocks until it is.

std::string status = asyncResult.get();

}Multithreading

The key concept behind using std::async and std::future is multithreading. Multithreading is a programming model where multiple sequences of instructions, called threads, can run concurrently within the same program.

In our Sort() example, we use std::async() to identify a discrete block of work that can be performed independently of the work we're doing in the "main thread". These secondary threads are typically called "worker threads".

CPU Cores

Modern consumer CPUs tend to have 8-24 cores, and each each core can physically work on 1-2 threads at the same time.

However, across all the programs running on a system, there might be thousands of threads looking to be processed. The operating system juggles threads in and out of cores to keep everyone happy.

Most threads aren't very demanding, so there's usually a lot of capacity left over.

The operating system will happily fill these slots with our program's work to help it complete faster.

But, when all of our work is structured as a single thread, the best it can do is put that thread in a single core and keep it there. To use more capacity, we need to use more threads.

The Risks

Memory management is currently the reigning champion of C++ bugs, but only because the true heavyweight contender - concurrency - is a beast that most developers dare not wake. Concurrency is very difficult.

It introduces whole new classes of problems and levels of complexity. When there are 20 different parts of our program running at the same time, interacting with the same resources, how can we possibly understand the overall state?

We can read a variable, read the exact same variable again, and it might have changed:

std::cout << x; // logs 32

std::cout << x; // logs 7298One thread can be iterating through an array of players; a second wants to sort the array by score; a third wants to update some scores. Things get chaotic fast.

Highly concurrent projects invest a lot of engineering effort into building the systems to manage all of this complexity.

The std::async Abstraction

We're using the simple std::async helper in this introductory course, which lets us weave concurrency patterns into our code incrementally in a relatively safe and controlled way.

Every time we have a function that is doing some heavy work, we can ask "is there an opportunity to offload some of this to another thread?"

Using concurrency in the small, controlled environment of a single function body makes it less likely we'll make a mistake. We trigger the async behavior - creating the std::async - and we return to the safe, synchronous world - calling .wait() - all within the same block of code.

In that context, it's usually pretty clear when our threads might be in conflict. Consider this attempt to sort a list of players in the background that also tries to to read and update that same data.

Because it is all happening within the same function body, it's easier to spot that we might be doing something problematic:

#include <vector>

#include <algorithm>

#include <future>

#include <string>

#include <iostream>

struct Player {

int score;

};

void Sort(std::vector<Player>& players) {

auto task = std::async([&players](){

std::ranges::sort(players, {}, &Player::score);

return std::string("Sort complete");

});

// Wait, my async task is working on this data!

Player PlayerOne = players[0];

// Wait, my async task is working on this data!

players[0].score += 10;

task.wait();

}This is the classic data race problem. We have no idea what PlayerOne is; we have no idea which player had their score increased; and we have no idea if our container even sorted properly.

However, because we can see the async launch and the data access in the same scope, these bugs are easier to spot.

It also means the async behavior doesn't "leak" into other parts of the program. When our function waits for its async tasks to complete before returning control, that function just becomes a regular, synchronous function as far as the outside world is concerned.

Someone calls it, and when they get control back, they know the work is done. From their perspective, it's just a normal function:

void Sort(std::vector<Player>& players) {

auto task = std::async([&players](){

std::ranges::sort(players, {}, &Player::score);

return std::string("Sort complete");

});

// Do other work if needed...

// Block here - don't return control until

// the sort is complete

task.wait();

}

void SafeProcess(std::vector<Player>& players) {

// This function spawns threads, but it waits

// for them to finish

Sort(players);

// I now know players have been sorted and can

// continue my work safely

int lowest_score = players[0].score;

}Increasing the Capability (and Danger)

Let's look at the next step up in capability, with an associated increase in design complexity and risk. The function that creates the task doesn't have to wait for it to complete before returning control. Instead, it can return the std::future.

This allows the caller to decide when to wait.

// Returns a future, doesn't block

std::future<void> Sort(std::vector<Player>& players) {

return std::async([&players](){

std::ranges::sort(players, {}, &Player::score);

return std::string("Sort complete");

});

}This is an important, fundamental change in how the function works, and the callers need to be aware. The return type gives them a hint, but it's common to also reflect the async nature within the function name.

This is usually done by adding a word like async to the name:

std::future<void> Sort (std::vector<Player>& players) {

std::future<void> SortAsync(std::vector<Player>& players) {

return std::async([&players](){

std::ranges::sort(players, {}, &Player::score);

return std::string("Sort complete");

});

}At the call site, the implications of using this function should now be clear:

void Caller(std::vector<Player>& players) {

// This might return faster than Sort()

SortAsync(players);

// ...but we don't know if the work has been completed yet

// We have no idea what players[0] is because

// the data may still be getting sorted

int lowest_score = players[0].score;

}The key benefit of our change is that it now gives the caller flexibility. The original Sort() forced them to wait, but SortAsync() lets them decide:

#include <vector>

#include <future>

void ProcessPlayers(std::vector<Player>& players) {

// Option 1: I still want to wait before continuing

SortAsync(players).wait();

// This is now safe

int lowest_score = players[0].score;

// Option 2: I want to wait, and I also want the result

std::string result = SortAsync(players).get();

// Option 3: I want to do other stuff while I wait

std::future<std::string> task = SortAsync(players);

DoOtherStuff();

// Sync up after using option 3

task.wait();

}Don't underestimate the risk of concurrency-related issues. As the asynchronous behavior begins to span across logical boundaries like function bodies, the complexity gets increasingly difficult to manage.

The nature of the resulting bugs makes them particularly insidious, too. It's very easy to write code that assumes task A will complete before task B without even realizing we've created a race. Even worse, that assumption might be correct 99.99% of the time, so we can test our code a thousand times and never encounter the bug.

But when we ship it and its now running billions of times, those 0.01% outcomes will be happening very frequently.

More Examples

Let's look at some more advanced uses and considerations for std::async.

Launch Policies

By default, std::async doesn't necessarily use multithreading. It's just a way to package up some work that could be multithreaded. It tells the underlying standard library implementation: "here's a discrete task that can safely be run on another thread, if you want".

This default flexibility allows std::async implementations to be conservative with thread creation if system resources are scarce. However, it can lead to unpredictable behavior, especially if you expect the task to start on a new thread immediately.

If you want to force the task to run on a new thread, you can specify the std::launch::async policy as the first argument:

std::future<void> SortAsync(std::vector<Player>& players) {

// Explicitly request a new thread

return std::async(std::launch::async, [&players](){

std::ranges::sort(players, {}, &Player::score);

return std::string("Sort complete");

});

}This is typically more useful that the default behavior. When we explicitly set up an asyncronous task, we're usually doing it because we know it's going to take a while to complete. In such cases, std::launch::async is preferred because it guarantees immediate (or near-immediate) execution on a new thread, making the concurrency behavior explicit and predictable.

Relying on the default makes the behavior of our program less deterministic. This is especially true if we want our code to be portable, as different implementations have different criteria for deciding when to create new threads. One might be more conservative than another, and we don't want the performance profile of our program to significantly change depending on which compiler built it.

Multiple Async Tasks

Our examples have been based around a single function creating a single async task, but we have as much flexibility as we want. We can spawn many async tasks, and those async tasks can also create their own.

A common pattern is to launch several independent tasks and then wait for all of them to complete. This is ideal for scenarios where you can split a larger problem into smaller, parallelizable chunks:

void ProcessFourThings() {

auto f1 = std::async(std::launch::async, []{ DoWork(); });

auto f2 = std::async(std::launch::async, []{ DoWork(); });

auto f3 = std::async(std::launch::async, []{ DoWork(); });

auto f4 = std::async(std::launch::async, []{ DoWork(); });

// Wait for all

f1.wait();

f2.wait();

f3.wait();

f4.wait();

}We can do this dynamically, perhaps using a std::vector to manage the std::future objects:

#include <vector>

#include <future>

#include <algorithm>

void ProcessBatch(int count) {

std::vector<std::future<void>> tasks;

tasks.reserve(count);

// 1. Launch all tasks

for (int i = 0; i < count; ++i) {

tasks.push_back(std::async(std::launch::async, []{

DoWork();

}));

}

// 2. Wait for all tasks

for (auto& task : tasks) {

task.wait();

}

}However, the creation of these tasks and the associated thread management has an overhead. If the work we need to do is relatively small, the cost of packaging it as a std::future can be greater than just doing the work.

As always, if something is performance-critical, we should benchmark our approach.

Benchmarking Multithreaded Code

When using multithreaded code in , there is some nuance we should be aware of in the results.

Let's imagine we have an algorithm that takes 10 milliseconds to run. We update it so 9 milliseconds of that CPU time is now done on a different thread:

#include <benchmark/benchmark.h>

#include <chrono>

#include <thread>

#include <future>

using namespace std::chrono;

void spin_for(duration){/*...*/}

// Terrible code

void SingleThreaded() {

spin_for(10ms);

}

// I can fix it

void MultiThreadedWork() {

auto task = std::async([](){

spin_for(9ms);

});

spin_for(1ms);

task.wait();

}

The benchmarks are going to be very impressed with our work. They will report we've made our code 10x more CPU efficient:

-------------------------------------

Benchmark Time CPU

-------------------------------------

BM_SingleThreaded 10.0 ms 10.0 ms

BM_MultiThreaded 9.03 ms 1.05 msThis is because the library prioritizes performance on the main thread, not all threads. In most real world scenarios, we share that priority, so this reported 10x improvement is often still valid.

This is because, when our performance becomes bottlenecked by the CPU, that is usually because of the main thread. There are other cores available with plenty of capacity - our program is just not structured in a way that can make use of it.

If we found a way to rewrite some part of the program such that that 90% of the work that was previously on the main thread can be moved out, that's pretty similar to 90% of the work just disappearing. We really have improved the real-world, observable performance.

Measuring Performance Across all Threads

If main thread performance isn't the priority, we can tell the library that we care about CPU usage across all threads using MeasureProcessCPUTime():

benchmarks/main.cpp

// ...

BENCHMARK(BM_SingleThreaded)->Unit(benchmark::kMillisecond);

BENCHMARK(BM_MultiThreaded)->Unit(benchmark::kMillisecond);

BENCHMARK(BM_MultiThreaded)

->Unit(benchmark::kMillisecond)

->MeasureProcessCPUTime();Now, the library reports that 10ms of CPU time was consumed across all cores - 1ms on the main thread and 9ms on the worker thread. The real-world processing time is still only 9ms due to the 1ms of concurrency:

-------------------------------------------------

Benchmark Time CPU

-------------------------------------------------

BM_SingleThreaded 10.0 ms 10.0 ms

BM_MultiThreaded 9.03 ms 1.05 ms

BM_MultiThreaded/process_time 9.03 ms 10.0 msSummary

In this lesson, we stepped into the world of concurrency, using multiple CPU cores to improve throughput.

- We used

std::asyncas our entry point to asynchronous tasks. It allows us to launch operations that can run on a separate thread, offloading heavy work from the main execution path. std::futureacts as a proxy for the result of an asynchronous task. It provides methods likewait()to block until completion andget()to retrieve the return value (or propagate exceptions).- We explored the concept of multithreading, understanding its benefits while also acknowledging the major risks.

std::launch::asynccan be used to explicitly force task execution on a new thread for predictable parallel behavior.- To benchmark multi-threaded code, we should distinguish between main thread CPU time and total process CPU time.

We have now seen how to use std::async for ad-hoc parallel tasks. But the C++ Standard Library offers even more specialized tools for parallelizing common algorithms.

In the next lesson, we will introduce execution policies, allowing us to simply tag standard algorithms like std::sort() with std::execution::par to automatically distribute their work across multiple CPU cores, without managing threads manually.

Parallel Algorithms and Execution Policies

Combine the elegance of C++20 Ranges with the power of parallel execution policies.