Momentum and Impulse Forces

Add explosions and jumping to your game by mastering momentum-based impulse forces

In this lesson, we'll explore how to implement physics interactions by adding momentum and impulses to our simulations.

We'll learn we can use physics to create features requiring sudden changes to motion, such as having our characters jump or get knocked back by explosions. We'll also learn how to modify the strength of those forces based on how far away the source of the force is.

Starting Point

This lesson continues to use the components and application loop we introduced earlier in the section. We'll mostly be working in the GameObject class we introduced previously.

The most relevant parts of this class to note for this lesson are its Tick() and ApplyForce() functions, as well as the Position, Velocity, Acceleration, and Mass variables.

src/GameObject.h

#pragma once

#include <SDL3/SDL.h>

#include <algorithm>

#include "Vec2.h"

#include "Image.h"

#include "Config.h"

class Scene;

class GameObject {

public:

GameObject(

const std::string& ImagePath,

const Vec2& InitialPosition,

const Scene& Scene ) : Image{ImagePath},

Position{InitialPosition},

Scene{Scene} {}

void HandleEvent(SDL_Event& E) {}

void Tick(float DeltaTime) {

ApplyForce(GetFrictionForce(DeltaTime));

ApplyForce(GetDragForce());

Velocity += Acceleration * DeltaTime;

Position += Velocity * DeltaTime;

Acceleration = {0, 9.8f * PIXELS_PER_METER};

Clamp(Velocity);

// Don't fall through the floor

if (Position.y > 200) {

Position.y = 200;

Velocity.y = 0;

}

}

void ApplyForce(const Vec2& Force) {

Acceleration += Force / Mass;

}

void Render(SDL_Surface* Surface);

private:

float DragCoefficient{0.2f};

Vec2 GetDragForce() const {

return -Velocity * Velocity.GetLength()

* DragCoefficient;

}

float GetFrictionCoefficient() const {

if (Position.y < 200) {

// Object isn't on the ground

return 0;

}

return 0.5f;

}

Vec2 GetFrictionForce(float DeltaTime) const {

float MaxMagnitude{GetFrictionCoefficient()

* Mass * Acceleration.y};

if (MaxMagnitude <= 0) return Vec2{0, 0};

float StoppingMagnitude{Mass *

Velocity.GetLength() / DeltaTime};

return -Velocity.Normalize() * std::min(

MaxMagnitude, StoppingMagnitude);

}

void Clamp(Vec2& V) const {

V.x = std::abs(V.x) > 0.1f ? V.x : 0.0f;

V.y = std::abs(V.y) > 0.1f ? V.y : 0.0f;

}

Vec2 Acceleration{0, 9.8f * PIXELS_PER_METER};

float Mass{50.0f};

Vec2 Position{0, 0};

Vec2 Velocity{0, 0};

Image Image;

const Scene& Scene;

};Momentum

Before we start adding to our class, there are two more concepts in physics we need to understand - momentum and impulse. Momentum is a combination of an object's velocity with its mass:

For example, if two objects have the same velocity, the heavier object will have more momentum. If a lighter object has the same momentum as a heavier object, that means the lighter object is moving faster.

Given that momentum is a mass multiplied by a velocity, the unit used to represent momentum will be a unit of mass (often kilograms, ) multiplied by a unit of velocity (often meters per second, ). When units are multiplied together, it's common to represent that multiplication using a center dot

For example:

- A object moving at has a momentum of

- A object moving at has a momentum of

- A object moving at also has a momentum of

Impulse

A change in an object's momentum is called an impulse. In game simulations, changes in momentum are almost always caused by changes in velocity, rather than a change in the object's mass.

As we've seen, a change in velocity requires acceleration, and acceleration is caused by a force being applied to an object for some period of time. Increasing the force, or applying the force for a longer duration, results in larger changes of momentum. Therefore:

Newton-Seconds

The unit used to measure momentum (and changes in momentum) is often referred to by an alternative, equivalent unit: the Newton-second, . For example:

- Applying of force for creates an impulse of

- Applying of force for creates an impulse of

- Applying of force for also creates an impulse of

Previously, we saw how a Newton is the amount of force required to accelerate a object by .

If we apply this acceleration for one second, the object's velocity will change by . And, given the object has of mass, its momentum will change by . Therefore, . Here are some more examples:

- of impulse will change a object's velocity by

- of impulse will change a object's velocity by

- of impulse will change a object's velocity by

Implementing Impulses

The time component of an impulse can be any duration but, in our simulations, the main use case for impulses is to apply instantaneous changes in momentum. That is, a force that is applied a single time, within a single tick of our simulation.

Examples of this might include letting our character jump off the ground or having objects react to an explosion.

The key technical difference between an instant impulse and a continuous force is that impulses should not be modified by our frame's delta time. A continuous force gets applied across many steps of our simulation, so its effect on each frame should depend on how much time has passed since the previous frame.

But an instant impulse is applied all within a single step, and its magnitude should not depend on how long that frame took to generate. Therefore, an implementation of impulses might look like this:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

// ...

private:

void ApplyImpulse(const Vec2& Impulse) {

Velocity += Impulse / Mass;

}

// ...

};Example: Jumping

Below, we use this mechanism to let our character jump when the player presses their spacebar.

In our physics simulation, we're using a scale where pixels equals meter, and our character has a mass of . To make the character jump upwards (negative Y) with a reasonable speed (e.g., 6 meters/second), we need to calculate the required impulse.

Using , if we want to be pixels/sec (6 meters/sec upwards), and is , then the impulse required is .

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

// ...

void HandleEvent(SDL_Event& E) {

if (E.type == SDL_EVENT_KEY_DOWN) {

if (E.key.key == SDLK_SPACE) {

// Apply upward impulse

ApplyImpulse({0.0f, -15000.0f});

}

}

}

// ...

};

Non-Instant Impulses

If we want to apply a force that continues for a fixed period of time, we can use our previous ApplyForce() technique, in conjunction with some mechanism that keeps track of time.

For example, we could use the SDL_Timer mechanisms we introduced previously, or accumulate time deltas that are flowing through our Tick() function until our accumulation has reached some target.

The following program uses the latter technique to apply a force for approximately 5 seconds:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

// ...

void Tick(float DeltaTime) {

ApplyForce(GetFrictionForce(DeltaTime));

ApplyForce(GetDragForce());

// Apply the timed force if active

if (ForceTimeRemaining > 0) {

ApplyForce({10000, 0});

ForceTimeRemaining -= DeltaTime;

}

Velocity += Acceleration * DeltaTime;

Position += Velocity * DeltaTime;

Acceleration = {0.0f, 9.8f * PIXELS_PER_METER};

Clamp(Velocity);

// Don't fall through the floor

if (Position.y > 200) {

Position.y = 200;

Velocity.y = 0;

}

}

// ...

private:

float ForceTimeRemaining{5.0f};

// ...

};Positional Impulses

So far, our examples have implemented forces such that our objects feel their full effect regardless of their position. This is reasonable for effects like gravity and jumping but, in many cases, we want to simulate forces that have a specific point of origin.

For example, we might have an explosion happening somewhere in the world, with the effect that objects are knocked away from that location.

As such, the direction of the effect of that force on each object depends on that specific object's position relative to where the explosion happened.

We can set that up by calculating the direction from the origin of the force to the position of our object, normalizing that vector so it has a magnitude of , and then multiplying it by the magnitude of the force we're applying:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

// ...

private:

void ApplyPositionalImpulse(

const Vec2& Origin, float Magnitude

) {

Vec2 Direction{(Position - Origin).Normalize()};

ApplyImpulse(Direction * Magnitude);

}

// ...

};Example: Explosions

Let's create an example where the player can click a position on the screen to create an explosion, knocking nearby objects away.

Our GameObject instances are currently receiving events within their HandleEvent() method, so we can access click events and the corresponding mouse position from there.

The force from an explosion is a quick, sudden blast. As such, we'll implement it as an immediate change in momentum using our ApplyPositionalImpulse() function. We'll pass the mouse coordinates to that function, alongside a magnitude that feels right. We'll use 100000 units of impulse, which is roughly enough to knock our character back at a speed of 40 meters/second if they are 1 meter away.

The following example applies the full effect of the force regardless of how far away it is from our object, but we'll implement distance falloff in the next section:

src/GameObject.cpp

#include <SDL3/SDL.h>

#include "GameObject.h"

void GameObject::Render(SDL_Surface* Surface) {

Image.Render(Surface, Position);

}

void GameObject::HandleEvent(SDL_Event& E) {

if (E.type == SDL_EVENT_MOUSE_BUTTON_DOWN) {

if (E.button.button == SDL_BUTTON_LEFT) {

ApplyPositionalImpulse(

Vec2{E.button.x, E.button.y},

10000.0f

);

}

} else if (E.type == SDL_EVENT_KEY_DOWN) {

if (E.key.key == SDLK_SPACE) {

if (Position.y > 200) return;

ApplyImpulse({0.0f, -15000.0f});

}

}

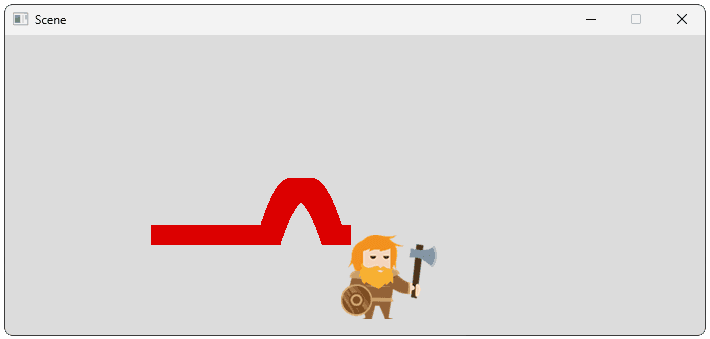

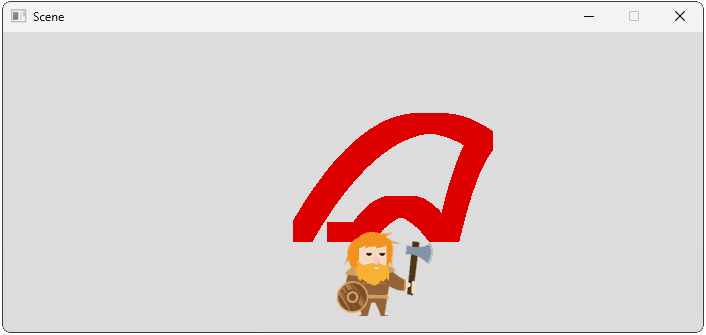

}Running our game, we should now see that any time we click in our window, our objects are knocked away from our mouse:

Note that the Position of our object currently represents the top left corner of its rendered image. We can change where our image is rendered relative to this position by updating the Render() function of our Image class. For example, the following moves our image up and to the left, such that the Position of our object is at the center of the image:

src/Image.h

// ...

class Image {

public:

// ...

void Render(

SDL_Surface* Surface, const Vec2& Pos

) {

if (ImageSurface) {

SDL_Rect Rect{

int(Pos.x),

int(Pos.x) - ImageSurface->w / 2,

int(Pos.y)

int(Pos.y) - ImageSurface->h / 2,

ImageSurface->w, ImageSurface->h

};

SDL_BlitSurface(

ImageSurface, nullptr, Surface, &Rect);

}

}

// ...

};Falloff and the Inverse-Square Law

An additional property of a force originating from a specific position, such as an explosion, is that objects closer to the explosion are affected more than objects further away.

To make our calculations simpler, when specifying the magnitude of a positional force, we specify it in terms of how that force will feel to an object that is one meter away from it.

For example, we might want to create an explosion where objects meter away experience of force. We'll represent that as .

The magnitude of the force experienced by objects at different distances follows the inverse-square law, where the effect falls off in proportion to the square of the distance.

As such, a function for calculating this falloff would look something like the following, where represents the distance between the explosion and the object that's reacting to it, and is the magnitude that would be experienced by an object one meter away:

Let's revisit our hypothetical explosion, where we defined to be . An object meters away from the same explosion will experience Newton of force as:

An object that is only centimeters ( meters) away will experience Newtons of force as:

Minimum Distance

The inverse-linear law is quite often a source of janky physics as, when the distance between an object and a force gets very small, the resulting magnitude of that force becomes extremely large.

If you've ever seen physics bugs where an object shoots off the screen at incredibly high speed, this division by a very small number was likely the cause.

To solve this, we intervene in our falloff calculation. A common solution is to add some small number to our distances - for example, .

Game simulations don't need to be entirely accurate - they just need to look right, and this tiny change isn't noticible when our objects are a normal distance apart. However, it makes a big difference when they're unrealistically close together:

Implementing Falloff

Let's update our ApplyPositionalImpulse() function to modify its effects based on the distance between our object and the origin of the force.

To make the physics calculations intuitive, we'll convert our distance from pixels to meters using our PIXELS_PER_METER constant before applying the inverse-square law. This ensures that "one meter away" actually means 50 pixels away in our game world.

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

// ...

private:

void ApplyPositionalImpulse(

const Vec2& Origin, float Magnitude

) {

Vec2 Displacement{Position - Origin};

Vec2 Direction{Displacement.Normalize()};

float DistancePixels{Displacement.GetLength()};

float DistanceMeters{DistancePixels / PIXELS_PER_METER};

// Apply inverse-square law with a small

// offset to prevent extreme forces

float AdjustedMagnitude{Magnitude /

((DistanceMeters + 0.1f) * (DistanceMeters + 0.1f))};

ApplyImpulse(Direction * AdjustedMagnitude);

}

// ...

};Complete Code

Our updated Scene, GameObject header, and GameObject source files are provided below.

The GameObject.cpp file also includes the code we used to draw trajectories in our screenshots for reference, but we'll walk through debug drawing in more detail later in the course.

Files

Summary

This lesson explores implementing momentum and impulses in our physics system, enabling instantaneous forces like jumps and explosions.

We've learned how to calculate the effects of these forces on objects with different masses and at varying distances. Key takeaways:

- Momentum is the product of mass and velocity, measured in or Newton-seconds, .

- Impulse represents a change in momentum and equals force multiplied by time.

- Instantaneous impulses apply forces within a single frame without being affected by delta time.

- Positional impulses allow for effects like explosions where force originates from a specific point.

- Force falloff follows the inverse-square law, making objects closer to the origin experience stronger effects.

- Adding a small offset to distance calculations prevents extreme forces when objects are very close to the origin.

Bounding Boxes

Discover bounding boxes: what they are, why we use them, and how to create them