Physical Motion

Create realistic object movement by applying fundamental physics concepts

In this lesson, we'll explore fundamental physics principles and how to implement them in our games. We'll explore how to represent position, velocity, and acceleration using our vector system, and how these properties interact over time.

By the end, you'll understand how to create natural movement, predict object trajectories, and integrate player input with physics systems.

Our starting point is includes Scene, GameObject, and Vec2 types using the same techniques we covered previously:

Starting Point

If you want to follow along, our starting point is provided below, which uses Window, Image, Scene, GameObject, and Vec2 types using techniques we covered previously.

Our code examples are using a dwarf.png image that is stored alongside our executable. Our screenshots are using free stock art available at this link, but any image will work.

Files

Position and Displacement

Previously, we've seen how we can represent the position of an object in a 2D space by using a 2D vector:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

// ...

Vec2 Position;

// ...

};The initial positions of our GameObject instances are set through the constructor. Our Scene object sets these initial positions when it constructs our GameObjects. For example, our Dwarf might be placed at , :

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

public:

Scene() {

Objects.emplace_back(

"dwarf.png", Vec2{100, 50}, *this

);

}

// ...

};Specifically, this is the object's position relative to the origin of our space. This is sometimes referred to as its displacement.

Units

When working with physics systems, it can be helpful to assign some real-world unit of measurement to this displacement.

However, since we are rendering directly to the screen, our units are inherently pixels (or points, on high-DPI displays).

If we want to simulate real-world physics, it's helpful to incorporate real world units into our code, such as meters. We'll introduce more complex ways to represent this soon, but a simple approach, particularly for 2D games, is to define a constant scaling factor between pixels and meters.

For example, we'll say that 1 meter equals 50 pixels., and we'll store this in a location where we can easily share it across our code, such as a configuration header:

src/Config.h

#pragma once

inline constexpr float PIXELS_PER_METER{50.0f};With this scale, our window (which is 700 pixels wide) represents a world that is 14 meters wide ().

Let's position our dwarf character at (3, 2) meters in our world. Since our underlying system works in pixels, we'll multiply these values by our scaling factor:

src/Scene.h

// ...

#include "Config.h"

class Scene {

public:

Scene() {

Objects.emplace_back(

"dwarf.png",

Vec2{

3.0f * PIXELS_PER_METER,

2.0f * PIXELS_PER_METER

},

*this

);

}

// ...

};Remember, SDL's surfaces use a y-down coordinate system, where increasing the y coordinate corresponds to moving downwards.

A position vector of {150, 100} represents the object being displaced 150 pixels (3 meters) from the left edge, and 100 pixels (2 meters) from the top edge.

To visualize our object's motion, our screenshots include a red rectangle showing the object's Position on each frame:

We'll cover how to draw debug helpers like this in detail later in the course.

Advanced: User-Defined Literals

When our code contains literal values that represent units of measurement, it can be unclear what units are being used.

// 100 what? Pixels? Meters?

SomeObject.SetPosition({100, 0});Or, like in our case, we may need to manually write expressions such as 3.0f * PIXELS_PER_METER to perform the required conversions.

We can use user-defined literals to make this clearer. This allows us to replace such expressions with something like 3.0_meters:

Objects.emplace_back(

"dwarf.png",

Vec2{

3.0f * PIXELS_PER_METER,

3.0_meters

2.0f * PIXELS_PER_METER

2.0_meters

},

*this

);Behind the scenes, we provide a special function that implements the conversion. For example, we could define _meters to return the value multiplied by PIXELS_PER_METER, so the literal 3.0_meters would evaluate to the floating point number 150.0.

User-defined literals to support both _pixels and _meters might look something like this:

src/Config.h

#pragma once

inline constexpr float PIXELS_PER_METER{50.0f};

// For floating-point literals like 10.5_pixels

float operator""_pixels(long double D) {

return static_cast<float>(D);

}

// For integer literals like 10_pixels

float operator""_pixels(unsigned long long D) {

return static_cast<float>(D);

}

// For floating-point literals like 2.5_meters

float operator""_meters(long double D) {

return static_cast<float>(D) * PIXELS_PER_METER;

}

// For integer literals like 2_meters

float operator""_meters(unsigned long long D) {

return static_cast<float>(D) * PIXELS_PER_METER;

}We have a dedicated lesson on if you want to learn more.

Velocity

Velocity is the core idea that allows our objects to move. That is, a velocity represents a change in an object's displacement over some unit of time.

We've chosen meters as our base unit of position, and we'll commonly use seconds, , as our unit of time. As such, velocity will be measured in meters per second.

As movement has a direction, our velocity will also have a direction, so we'll use our Vec2 type. For example, if an object's velocity is {x = 100, y = 0}, our object is moving 100 pixels (2 meters) to the right every second:

src/GameObject.h

#include "Config.h"

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

// ...

// 100 pixels/sec right

Vec2 Velocity{2.0f * PIXELS_PER_METER, 0.0f};

// ...

};We can implement this behavior in our Tick() function. Our velocity represents how much we want our displacement to change every second, but our Tick() function isn't called every second. Therefore, we need to scale our change in velocity by how much time has passed since the previous tick.

We can do this by multiplying our change by our tick function's DeltaTime argument (which is in seconds):

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

// ...

void Tick(float DeltaTime) {

Position += Velocity * DeltaTime;

}

// ...

};

Our application should be ticking multiple times per second, so our DeltaTime argument will be a floating point number between 0 and 1. Multiplying a vector by this value will have the effect of reducing its magnitude but, after one second of tick function invocations, we should see our displacement change by approximately the correct amount.

We can temporarily add a Time variable and some logging to confirm this:

// ...

#include <iostream> // For std::cout

class GameObject {

public:

// ...

float Time{0};

void Tick(float DeltaTime) {

Position += Velocity * DeltaTime;

Time += DeltaTime;

std::cout << "\nt = " << Time

<< ", Position = " << Position;

}

// ...

};From to , our character moved by approximately 100 pixels (2 meters) horizontally as expected:

t = 0.0223181, Position = { x = 150.011, y = 100 }

t = 0.0360435, Position = { x = 150.163, y = 100 }

...

t = 0.9969611, Position = { x = 249.996, y = 100 }

t = 1.0000551, Position = { x = 250.031, y = 100 }Speed

The concepts of speed and velocity are closely related. The key difference is that velocity includes a notion of direction, whilst speed does not. Accordingly, velocity requires a more complex vector type, whilst speed is a simple scalar, like a float or an int.

To calculate the speed associated with a velocity, we simply calculate the length (or magnitude) of the velocity vector. So, in mathematical notation, .

Below, we calculate our speed based on the object's Velocity variable. We also do some vector arithmetic comparing the object's previous position to its new position, confirming our simulation really is moving our object at that speed:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

// ...

void Tick(float DeltaTime) {

Vec2 PreviousPosition{Position};

Position += Velocity * DeltaTime;

std::cout << "\nIntended Speed = "

<< Velocity.GetLength()

<< ", Actual Speed = "

<< Position.GetDistance(PreviousPosition)

/ DeltaTime;

}

//...

};Intended Speed = 100, Actual Speed = 100.0005

Intended Speed = 100, Actual Speed = 99.9974

...It's often required to perform this calculation in the opposite direction, where we want to travel at a specific speed in a given direction. Rather than defining a Velocity member for our objects, we could recreate it on-demand by multiplying a direction vector by a movement speed scalar:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

// ...

Vec2 Direction{1, 0};

float MaximumSpeed{2.0f * PIXELS_PER_METER};

// Now calculated within Tick()

Vec2 Velocity{2.0f * PIXELS_PER_METER, 0.0f};

void Tick(float DeltaTime) {

Vec2 PreviousPosition{Position};

Vec2 Velocity{

Direction.Normalize() * MaximumSpeed

};

Position += Velocity * DeltaTime;

std::cout << "\nIntended Speed = "

<< MaximumSpeed

<< ", Actual Speed = "

<< Position.GetDistance(PreviousPosition)

/ DeltaTime;

}

};Intended Speed = 100, Actual Speed = 100.004

Intended Speed = 100, Actual Speed = 99.9993

...We covered how to use vectors to define movement in more detail .

Acceleration

Just as velocity is the change in displacement over time, acceleration is the change in velocity over time.

Therefore, let's figure out what the units of acceleration should be:

- Displacement is measured in meters:

- Velocity, as the change in displacement over time, is measured in meters per second:

- Acceleration, as the change in velocity over time, is measured in meters per second per second: . This is equivalent to , usually written as

Acceleration also has a direction, so is typically represented by a vector:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

// ...

// Accelerate 1m/s^2 (50 pixels/s^2) to the left

Vec2 Acceleration{-1.0f * PIXELS_PER_METER, 0.0f};

// ...

};Much like how we used the velocity to update an object's displacement on tick, we can use acceleration to update an object's velocity:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

// ...

void Tick(float DeltaTime) {

Velocity += Acceleration * DeltaTime;

// Unchanged

Position += Velocity * DeltaTime;

}

// ...

};Deceleration

Acceleration doesn't necessarily cause an object's speed to increase. If the direction of acceleration is generally in the opposite direction to the object's current velocity, that acceleration will cause the speed to reduce.

That is the case in our example, where the character's initial velocity is to the right (x = 100 in the Velocity vector) but is accelerationg leftwards (x = -50 in the Acceleration vector)

Over two seconds, this acceleration will have reduced Velocity.x to 0, meaning the object momentarily stops moving.

From then on, the acceleration and velocity are both pointing left, so the object's velocity starts to increase again, but now in the opposite direction. Four seconds into the simulation, the object's Velocity.x will be -100, meaning it is traveling at the same speed it started with, but now in the opposite direction.

If the acceleration doesn't change, the object will continue to move at ever-increasing speed in the leftward (negative x) direction.

Gravity

The most common accelerative force we simulate is gravity - the force that causes objects to fall to the ground. On Earth, the acceleration caused by gravity is approximately towards the ground.

Remember, moving down in our coordinate system corresponds to increasing y values so, to simulate earth-like gravity in our game, we would use a positive y acceleration:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

// ...

Vec2 Acceleration{

// No horizontal acceleration

0,

// Gravity pointing down (+y)

9.8f * PIXELS_PER_METER

};

// ...

};Trajectories

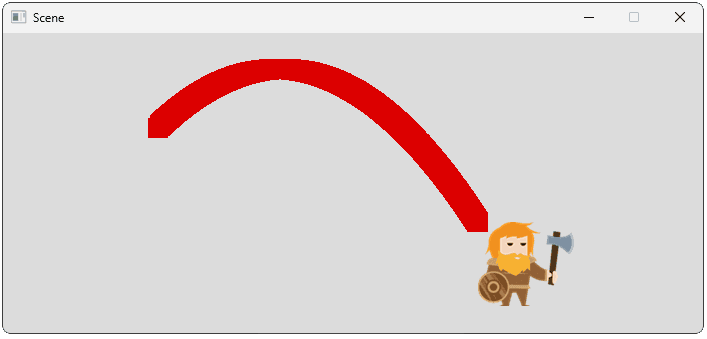

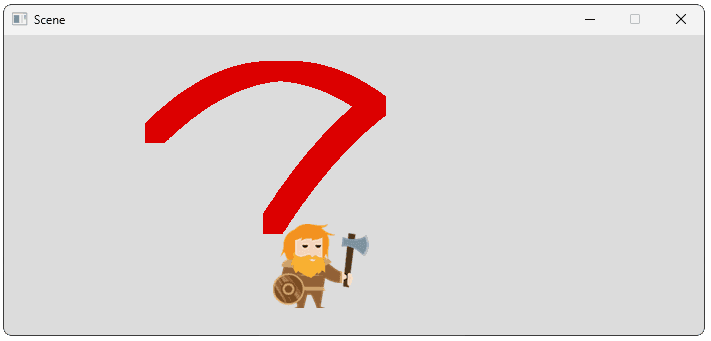

A trajectory is the path that an object takes through space, given its initial velocity and the accelerative forces acting on it. The most common trajectory we're likely to recognize is projectile motion.

For example, when we throw an object, we apply some initial velocity to it and, whilst it flies through the air, gravity is constantly accelerating it towards the ground.

This causes the object to follow a familiar, arcing trajectory:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

// ...

// Up and Right

Vec2 Velocity{

4 * Config::PIXELS_PER_METER,

-6 * Config::PIXELS_PER_METER

};

// Gravity Down

Vec2 Acceleration{

0,

9.8 * Config::PIXELS_PER_METER

};

// ...

};

The Relationship Between Displacement, Velocity, and Acceleration

In the previous sections, we saw that acceleration updates velocity, and velocity updates displacement. It's important to understand how these interact and compound.

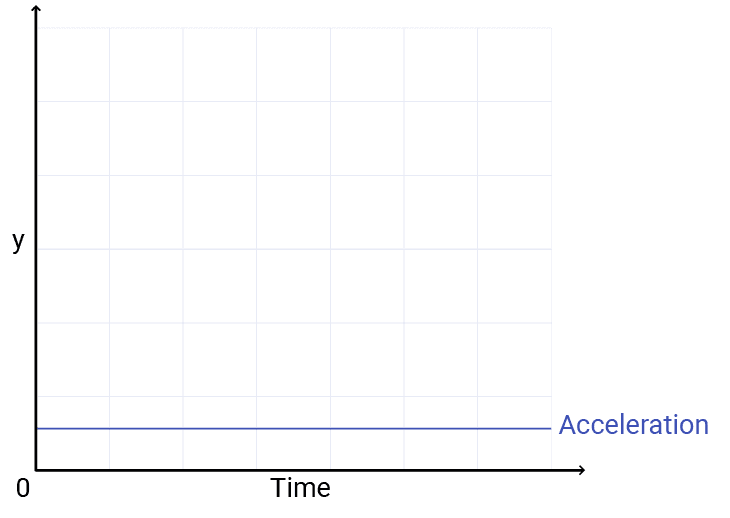

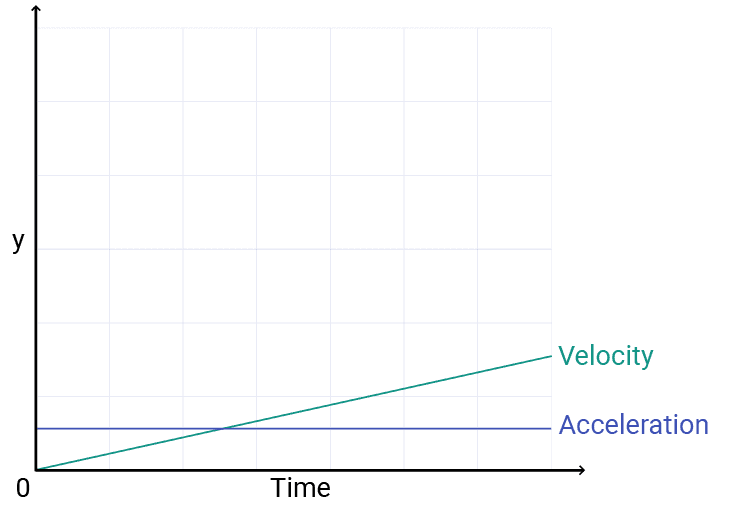

For example, imagine we have an acceleration that is pointing downwards (in the positive direction) with a magnitude that is not changing over time. On a chart, our acceleration value would be represented as a straight line:

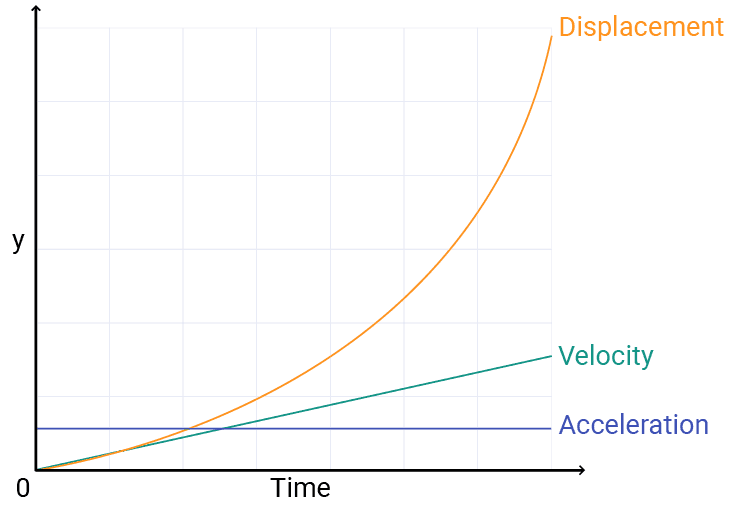

However, as long as the acceleration is not zero, it is continuously changing our velocity value over time. So, a constant acceleration results in a linear change in velocity:

But velocity is also changing our displacement over time. If our velocity is constantly increasing, that means our displacement is not only changing over time, but the rate at which it is changing is also increasing. On our chart, the exponential increase looks like this:

In the next lesson, we'll introduce concepts like drag and friction, which counteract these effects and ensure that the effect of acceleration doesn't result in velocities and displacements that quickly scale towards unmanageably huge numbers.

Combining Player Input with Physics

When making games, our physics simulations typically need to interact in a compelling way with user input. For example, if our player tries to move their character to the left, we need to intervene in our physics simulation to make that happen.

There is no universally correct way of doing that - the best approach just depends on the type of game we're making, and what feels most realistic or fun when we're playing.

A common approach is to have player input directly update one or more of our three key variables - position, velocity, or acceleration. This is usually easy to set up as, within each frame, player input is processed before the physics simulation updates. In our context, that means that HandleEvent() happens before Tick(). Below, we let the player set the horizontal component of their character's velocity before the physics simulation ticks:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

// ...

void HandleEvent(SDL_Event& E) {

if (E.type == SDL_EVENT_KEY_DOWN) {

switch (E.key.key) {

case SDLK_LEFT:

Velocity.x = -4.0f * PIXELS_PER_METER;

break;

case SDLK_RIGHT:

Velocity.x = 4.0f * PIXELS_PER_METER;

break;

}

}

}

// ...

};Player input can now be incorporated into our simulation:

Later in this chapter, we'll cover some alternative techniques for this. We'll also add collisions in our physics simulations, which will stop the player from running through walls or falling through the floor.

Equations of Motion and Motion Prediction

Naturally, a lot of research and academic effort has been made investigating and analyzing the physical world. We can apply those learnings to our own projects when we need to simulate natural processes, such as the motion of objects.

Some of the most useful examples are the SUVAT equations. In scenarios where our acceleration isn't changing, the SUVAT equations establish relationships between 5 variables:

- is displacement

- is the initial velocity

- is the final velocity

- is acceleration

- is time

The equations are as follows:

For example, if we know an object's current position, current velocity, and acceleration, we can predict where it will be in the future using the second equation:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

float u{1}; // velocity

float a{1}; // acceleration

float t{10}; // time

// displacement

float s = u * t + 0.5 * a * t * t;

std::cout << "In " << t << " seconds I "

"predict I will have moved "

<< s << " meters";

float CurrentDisplacement{3};

std::cout << "\nMy new displacement would be "

<< CurrentDisplacement + s << " meters";

}In 10 seconds I predict I will have moved 60 meters

My new displacement would be 63 metersHow accurate the prediction will be depends on how much the acceleration changes over the time interval. If the acceleration doesn't change at all, our prediction will be exactly correct.

Using Vectors

Our previous equations and examples were using scalars for displacements, velocities, and acceleration. This is fine if we only care about motion in a straight line, but what about motion in a 2D or 3D space?

Thanks to the magic of vectors, we can drop them straight into the same equations:

#include <iostream>

#include "Vec2.h"

int main() {

Vec2 u{100, 200}; // Initial velocity

Vec2 a{100, 200}; // Acceleration

float t{10}; // time

// Displacement

Vec2 s = u * t + a * t * t * 0.5f;

std::cout << "In " << t << " seconds I "

"predict I will have moved "

<< s << " pixels";

}In 10 seconds I predict I will have moved { x = 6000, y = 12000 } pixelsAdvanced: Vector Notation

The equivalent to all of the SUVAT equations using vectors is below.

There are two things to note from the vector form of these equations.

Firstly, the time variable () is a scalar, whilst all other variables are vectors. It's common in mathematical notation to make vector variables bold

Secondly, has been slightly modified from its scalar counterpart . This is to remove some ambiguity associated with vector multiplication.

Advanced: Vector Multiplication

A vector product is the result of multiplying two vectors together. Scalar multiplication, as in , only has a single definition, but there are two different forms of vector multiplication:

- The cross product, which uses the symbol, as in .

- The dot product, which uses the symbol, as in

The cross product of two vectors returns a new vector that is perpendicular to both of them. This concept isn't defined when our vectors only have two dimensions, but it has some utility for three-dimensional simulations.

The dot product tends to be more useful. The dot product of two vectors is calculated by multiplying their corresponding components, and then adding those results together.

For example, the dot product of the vectors and is :

Generalizing to any pair of 2D vectors, the equation looks like this:

We could add a Dot() method to our Vec2 type like this:

src/Vec2.h

// ...

struct Vec2 {

// ...

float Dot(const Vec2& Other) const {

return (x * Other.x) + (y * Other.y);

}

};

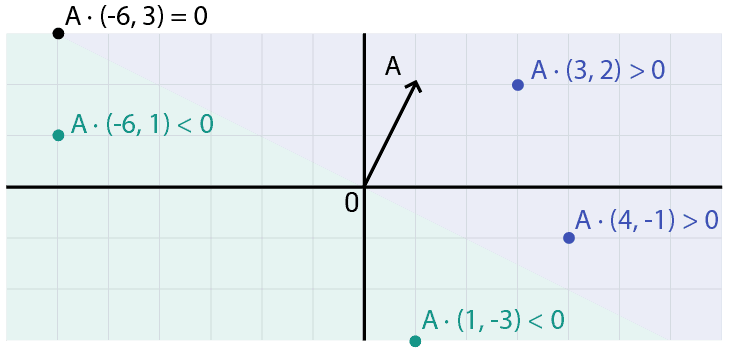

// ...We won't need the dot product in this course, but it has useful properties that are widely used to solve problems in computer graphics and game simulations. For example, the dot product can tell us the extent to which a vector is "facing" another vector:

- If a direction vector is pointing toward a position vector, their dot product will be positive

- If a direction vector is pointing away from a position vector, their dot product will be negative

- If the vectors are exactly perpendicular, their dot product will be

For example, we might have a character looking up and to the right. The direction they're facing is represented by the arrow in this diagram:

Vectors positioned in the blue area have a positive dot product with , meaning they're "in front" of our character.

We could use this as part of a calculation to determine whether a character is in some other character's line of sight:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

// ...

// Where am I?

Vec2 Position;

// Which direction am I facing?

Vec2 Direction{1, 0};

bool CanSee(const GameObject& Target) const {

// The vector from me to the target

Vec2 ToTarget{Target.Position - Position};

return

// Target is close to me...

ToTarget.GetLength() < 10

// ...and target is in front of me

&& Direction.Dot(ToTarget) > 0;

}

// ...

};If we normalize our two vectors (that is, set their magnitude to ), then their dot product will be in the range to . This gives us an easy way to determine the exact extent to which two vectors point in the same direction: from (directly opposite) to (exact same direction)

A more detailed introduction to the dot product of two vectors is available at mathisfun.com.

Summary

Physics is the backbone of realistic movement in games. In this lesson, we've explored how to implement fundamental motion physics in C++ using SDL3, transforming static objects into dynamic entities that behave naturally. Key takeaways:

- Position is represented by a 2D vector in screen space (pixels).

- Velocity is the rate of change in position (pixels/second).

- Acceleration is the rate of change in velocity (pixels/second).

- To simulate real-world values like gravity, we give our space a real world scale (e.g., 50 pixels = 1 meter).

- The

Tick(DeltaTime)function is where motion integration happens: updating velocity by acceleration, and position by velocity. - Player input can be mapped directly to changes in velocity or acceleration.

- Standard equations of motion have many applications, including to predict future positions.

Force, Drag, and Friction

Learn how to implement realistic forces like gravity, friction, and drag in our physics simulations using SDL3.