Handling Object Collisions

Implement bounding box collision detection and response between game objects

In this lesson, we'll revisit our physics system and integrate our new bounding boxes and rectangle intersection tools to allow objects to interact with each other.

We'll start by adding a floor object, and we'll use bounding box intersections to detect when our object hits the floor (or anything else).

Finally, we'll code the logic to react to these collisions appropriately, with behaviors such as preventing objects from overlapping or reducing our player's health if they get hit by a projectile.

Currently, we're simulating the effects of gravity, which is constantly accelerating objects towards the floor of our world. However, we don't really have a "floor" - we're just faking it by limiting our object's y position:

src/GameObject.cpp

// ...

void GameObject::Tick(float DeltaTime) {

Velocity += Acceleration * DeltaTime;

Position += Velocity * DeltaTime;

Acceleration = {0, 9.8f * PIXELS_PER_METER};

Clamp(Velocity);

// Don't fall through the floor

if (Position.y > 200) {

Position.y = 200;

Velocity.y = 0;

}

Bounds.SetPosition(GetPosition());

}

// ...Let's improve this by introducing an object that represents our floor, and prevents other objects from falling through it. We'll do this using our new bounding boxes and intersection tests, rather than the hard-coded assumption that the ground's y-position is always 200.

Adding Stationary Objects

Let's add an object to our scene to represent our floor. We typically don't want our floor and similar objects to be affected by gravity or movable in general. To handle this, we'll add an isMovable boolean to our GameObject class:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

GameObject(

const std::string& ImagePath,

const Vec2& InitialPosition,

float Width,

float Height,

const Scene& Scene,

bool isMovable = false

) : Image{ImagePath},

Position{InitialPosition},

Scene{Scene},

isMovable{isMovable},

Bounds{SDL_FRect{

InitialPosition.x, InitialPosition.y,

Width, Height

}}

{}

// ...

private:

// ...

bool isMovable;

};Within our Tick() function, we'll skip all of our physics simulations for stationary objects:

src/GameObject.cpp

// ...

void GameObject::Tick(float DeltaTime) {

if (!isMovable) return;

}

// ...Let's update our Scene to make our dwarf movable, and construct an immovable object representing our floor:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

public:

Scene() {

Objects.emplace_back(

"dwarf.png",

Vec2{

2 * PIXELS_PER_METER,

4 * PIXELS_PER_METER

},

1.9f * PIXELS_PER_METER,

1.7f * PIXELS_PER_METER,

*this,

true

);

Objects.emplace_back(

"floor.png",

Vec2{

3 * PIXELS_PER_METER,

5 * PIXELS_PER_METER

},

4 * PIXELS_PER_METER,

2 * PIXELS_PER_METER,

*this,

false

);

}

// ...

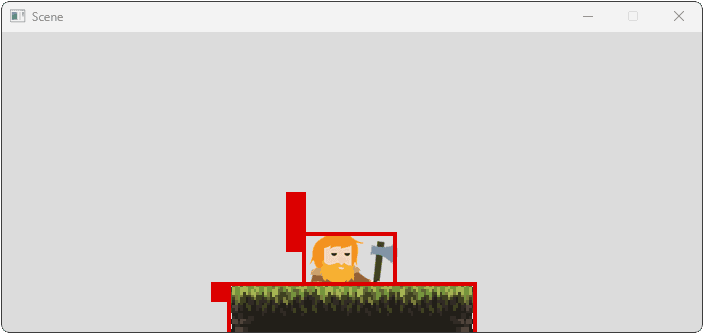

};We should now see both of our objects rendered. However, our character will fall straight past our new floor object until it reaches our hardcoded Position.y > 200 check.

Collision Checks

To determine what an object is colliding with, the object will need access to the things within our scene. We'll add a getter to our Scene to provide this access.

We'll also add some type aliases to reduce the amount of noise in our Scene class:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

public:

// ...

const std::vector<GameObject>& GetObjects() const {

return Objects;

}

// ...

};Within our GameObject class, we'll add a HandleCollisions() function:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

// ...

private:

// ...

void HandleCollisions();

};We'll call it within our Tick() function. We'll also remove our rudimentary floor check, as our HandleCollision() function will take care of it eventually:

src/GameObject.cpp

// ...

void GameObject::Tick(float DeltaTime) {

// Don't fall through the floor

if (Position.y > 200) {

Position.y = 200;

Velocity.y = 0;

}

Bounds.SetPosition(GetPosition());

HandleCollisions();

}

void GameObject::HandleCollisions() {

// ...

}

// ...Running our game, we should now see that our player immediately falls through the floor and off the bottom of our screen:

To solve this problem, we first need to detect when our character hits the floor. Earlier in the chapter, we added bounding boxes to our GameObject instances so, to understand which objects are colliding, we need to check which bounding boxes are intersecting.

Let's do this within our HandleCollisions() function:

src/GameObject.cpp

// ...

#include <iostream> // for std::cout

// ...

void GameObject::HandleCollisions() {

for (const GameObject& O : Scene.GetObjects()) {

// Prevent self-collision

if (&O == this) continue;

SDL_FRect Intersection;

if (Bounds.GetIntersection(

O.Bounds, &Intersection

)) {

std::cout << "Collision Detected\n";

// Handle Collision...

} else {

std::cout << "No Collision\n";

}

}

}We should now see collisions being detected. Eventually, our player will completely fall through the floor to the space below it, at which point their bounding boxes will no longer be overlapping:

Collision Detected

Collision Detected

Collision Detected

...

No Collision

No Collision

...Reacting to Collisions

Once we've detected a collision, we next need to understand how to react to it. The nature of our reaction depends entirely on our game and the mechanics we're trying to create.

Throughout the rest of this lesson, we'll cover many techniques to understand the nature of collisions so we can create more dynamic reactions. For now, though, the only possible collision our system could have detected was the character falling into the floor, so let's react to that.

The reaction to floor collisions is usually pretty standard across games - we resolve the overlap by moving our object out of the collision. When falling onto a surface, this typically means pushing our object upwards by decreasing its Position.y (remember, y increases downwards).

To understand how much we need to move y by, we need to determine how far our character has fallen into the floor. The most generally useful approach is to retrieve the intersection rectangle using a function like the GetIntersection() method we added to our BoundingBox class in the previous lesson.

Then, using the intersection rectangle calculated by GetIntersection(), we can determine the overlap depth. For a simple vertical collision (like landing on a floor), we push our object up by the height of that intersection (Intersection.h), thereby resolving the overlap and placing our object correctly on top of the surface it was colliding with.

We'll also reset the object's vertical velocity to 0, which we'll explain in the next section:

src/GameObject.cpp

// ...

void GameObject::HandleCollisions() {

for (const GameObject& O : Scene.GetObjects()) {

// Prevent self-collision

if (&O == this) continue;

SDL_FRect Intersection;

if (Bounds.GetIntersection(

O.Bounds, &Intersection

)) {

Position.y -= Intersection.h;

// See note below

Velocity.y = 0;

}

}

}Remember, the physics and collision reactions are all happening within the same frame - the player never sees our objects overlapping. It happens behind the scenes, and our HandleCollision() function resolves it before the player sees any overlap.

This is because we're resolving the collisions during the Tick() step, which comes before Render().

Note: Updating Velocity

In most cases, we should ensure we change the velocity of objects as a result of collisions, not just their position. Not setting velocity is a common source of bugs.

If we don't do it, our program can still appear to be working correctly. But, behind the scenes, the gravity acceleration is constantly increasing the velocity, and, eventually, it can get so high that our object can fully move through the floor within a single frame without the collision being detected.

Tracking when the Character is on the Ground

In many games, it's useful to know whether or not our character is currently on the ground. We can keep track of that using a new member variable, which our HandleCollisions() function can keep up to date.

By default, we'll assume an object is not on the ground on any given frame, unless our collision system detects that it is:

Files

To see this in action, we might update our HandleEvent() function to give our player the ability to jump if their character is currently on the ground:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

// ...

void HandleEvent(SDL_Event& E) {

if (E.type == SDL_EVENT_KEY_DOWN) {

if (E.key.key == SDLK_SPACE && isOnGround) {

ApplyImpulse({0.0f, -10000.0f});

}

}

}

// ...

}How Did I Collide?

A common requirement we will have when implementing our game logic is a need to understand not just when a collision happened, but the nature of that collision.

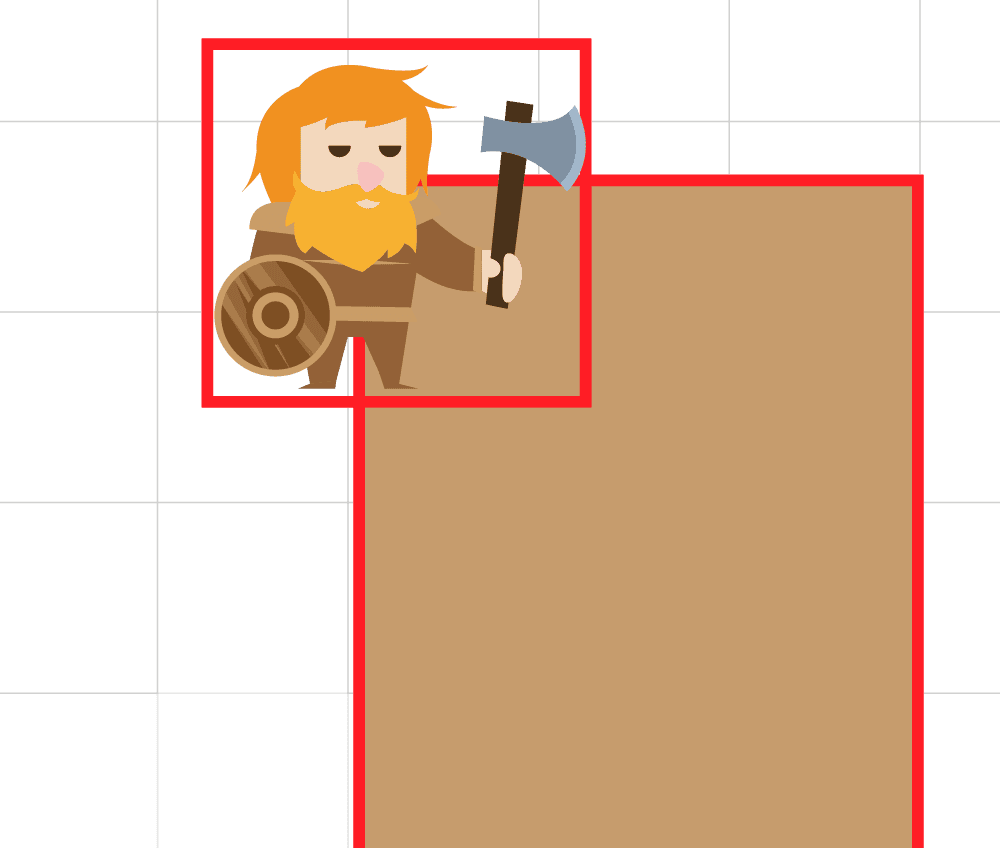

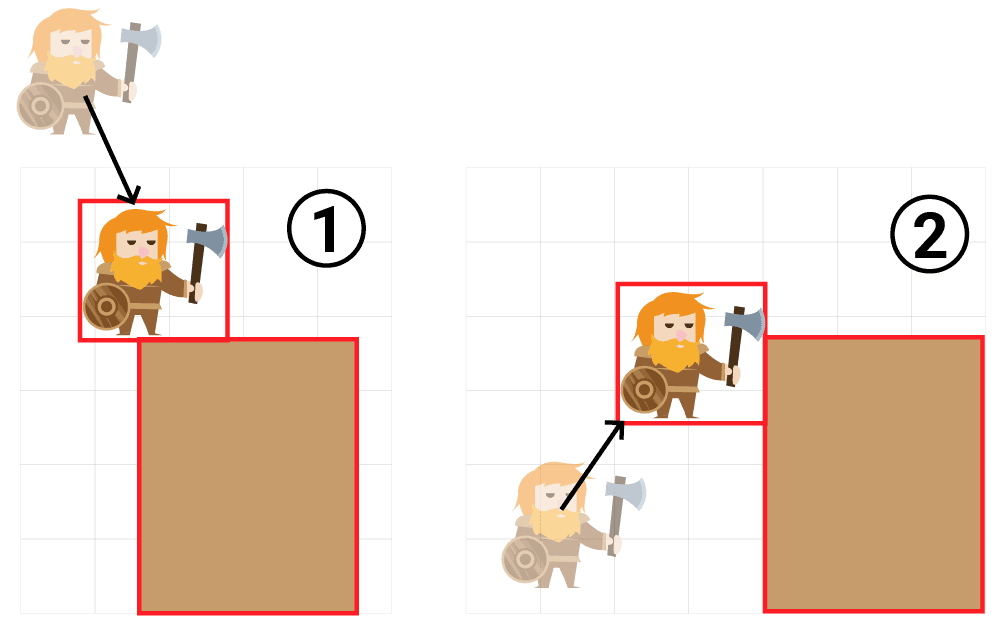

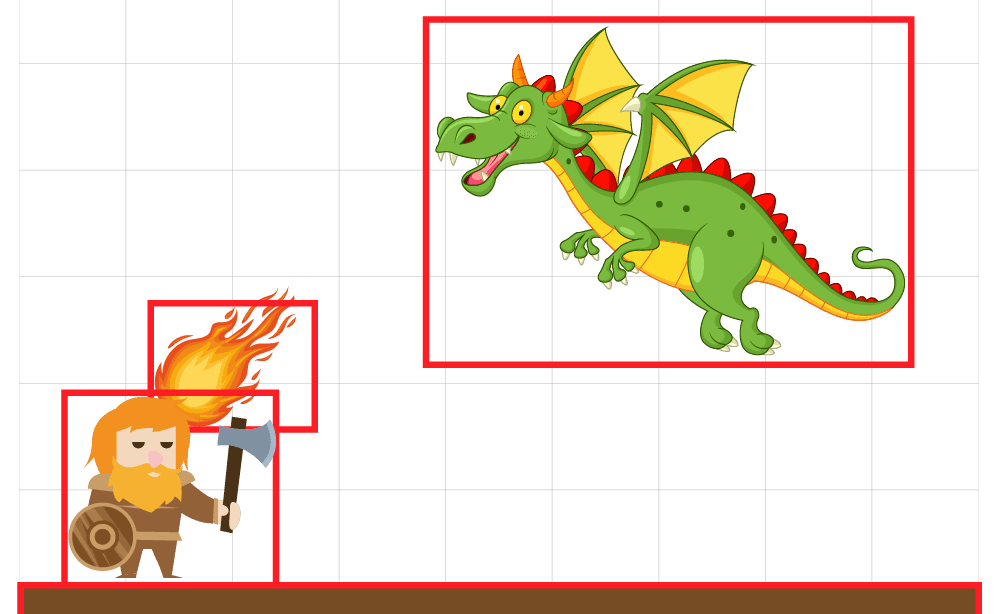

For example, our HandleCollisions() function may encounter a situation like the following:

It's not entirely clear how this should be resolved. If the player got into this situation by falling down, the expected resolution would be to push the character back up. But, if they got into this situation by jumping into the wall from the left, the natural response would be to push the character back to the left:

To understand how to resolve this situation, our HandleCollisions() function often needs to get a deeper understanding of how this situation arose. This might involve tactics like:

- Checking the velocity of the player

- Comparing the positions of the colliding objects

- Comparing the width and height of the intersection rectangle

Ultimately, how we react to any collision will be a judgment call based on the needs of our game. The following code shows some examples of how we can get more information on the nature of the collision, and the state of our objects when it happened:

GameObject.cpp

// ...

void GameObject::HandleCollisions() {

isOnGround = false;

for (const GameObject& O

: Scene.GetObjects()

) {

// Prevent self-collision

if (&O == this) continue;

SDL_FRect Intersection;

if (Bounds.GetIntersection(

O.Bounds, &Intersection

)) {

if (Velocity.x > 0) {

std::cout << "I was moving right\n";

}

if (Velocity.y >= 0) {

std::cout << "I wasn't falling\n";

}

if (Position.x < O.Position.x) {

std::cout << "I'm to the left of the "

"object I collided with\n";

}

if (Intersection.h > Intersection.w) {

std::cout << "The intersection is "

"mostly vertical\n";

}

std::cout << "I think I should be pushed "

"to the left";

Position.x -= Intersection.w;

}

}

}I was moving right

I wasn't falling

I'm to the left of the object I collided with

The intersection is mostly vertical

I think I should be pushed to the leftPrevious Position

We can also keep track of additional data to assist our collision system in determining how it should resolve collisions. A frequently useful addition is to keep track of both the previous position and the current position of the object.

Files

This lets our HandleCollisions() function retrieve both the Position and PreviousPosition of the object, which can further help it understand how it should react.

Multiple Colliders

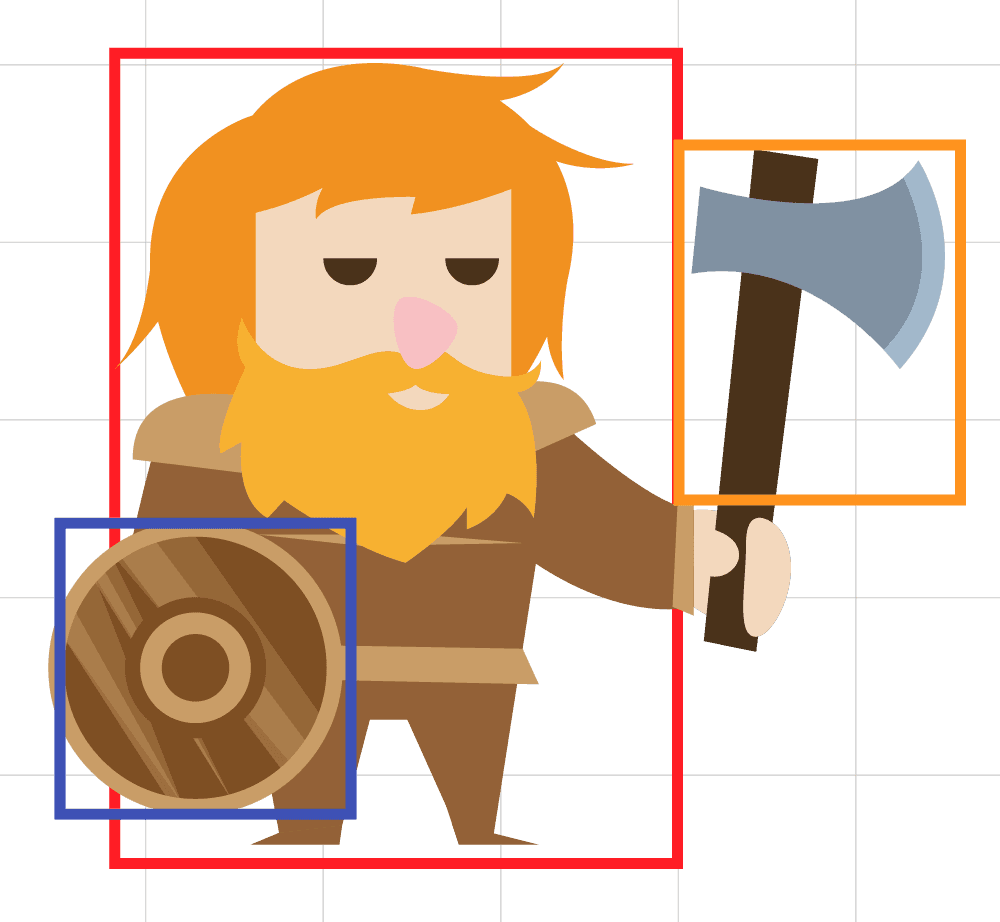

For more complex simulations, our object may need to be comprised of multiple bounding boxes. For example, we might need to determine if objects hit our player's weapon, shield, or body:

We can create many mechanics with a single bounding box and some clever logic.

For example, classic platformer games typically have mechanics where jumping on the head of an enemy defeats them, but hitting any other part causes the player to lose a life.

An intuitive approach to solve this problem might be to add separate bounding boxes for the head and the body, but this is rarely necessary. Instead, the illusion can be created with a single bounding box, and comparing the state of the objects at the time they intersect:

src/GameObject.cpp

// ...

void GameObject::HandleCollisions() {

isOnGround = false;

for (const GameObject& O

: Scene.GetObjects()

) {

// Prevent self-collision

if (&O == this) continue;

SDL_FRect Intersection;

if (Bounds.GetIntersection(

O.Bounds, &Intersection

)) {

if (Position.y < O.Position.y) {

std::cout << "I landed on his head";

}

}

}

}What Did I Collide With?

In a more complex game, our objects can collide with many different things, such as enemies, walls, and projectiles.

If the player collides with a wall, we might want to change their position but, if they collide with a projectile, perhaps we want to reduce their health instead.

In a real project, it is typically the case that our objects will use some form of component system (which we introduce in the next chapter) or inheritance based on a polymorphic base type.

With a polymorphic approach, we can add a virtual method for retrieving information as to the type of the object. Derived types can override those functions as needed.

In the following example, we add GetType(), GetTypeName() and HasType() functions to our GameObject base type. We then add Player, Floor, and Projectile base types that override them:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

enum class GameObjectType {

GameObject, Player, Projectile, Floor

};

class GameObject {

public:

virtual GameObjectType GetType() {

return GameObjectType::GameObject;

}

virtual std::string GetTypeName() {

return "GameObject";

}

bool HasType(GameObjectType TargetType) {

return GetType() == TargetType;

}

virtual ~GameObject() = default;

// ...

};

class Player : public GameObject {

public:

using GameObject::GameObject;

GameObjectType GetType() override {

return GameObjectType::Player;

}

std::string GetTypeName() override {

return "Player";

}

};

class Floor: public GameObject {

public:

using GameObject::GameObject;

GameObjectType GetType() override {

return GameObjectType::Floor;

}

std::string GetTypeName() override {

return "Floor";

}

};

class Projectile : public GameObject {

public:

using GameObject::GameObject;

GameObjectType GetType() override {

return GameObjectType::Projectile;

}

std::string GetTypeName() override {

return "Projectile";

}

};Implementing Polymorphism

To implement run-time polymorphism, systems like our Scene and physics code will be working with pointers or references to that polymorphic base type. For example, rather than managing a collection of GameObject instances, our Scene might manage a collection of GameObject pointers, or smart pointers:

src/Scene.h

// ...

#include <memory> // for std::unique_ptr

// Adding some type aliases to reduce noise

using GameObjectPtr = std::unique_ptr<GameObject>;

using GameObjects = std::vector<GameObjectPtr>;

class Scene {

public:

Scene() {

Objects.emplace_back(std::make_unique<Player>(

"dwarf.png",

Vec2{

2 * PIXELS_PER_METER,

4 * PIXELS_PER_METER

},

1.9f * PIXELS_PER_METER,

1.7f * PIXELS_PER_METER,

*this,

true

));

Objects.emplace_back(std::make_unique<Floor>(

"floor.png",

Vec2{

3.0f * PIXELS_PER_METER,

5.0f * PIXELS_PER_METER

},

2.0f * PIXELS_PER_METER,

2.0f * PIXELS_PER_METER,

*this,

false

));

}

const std::vector<GameObject>& GetObjects() const {

const GameObjects& GetObjects() const {

return Objects;

}

// ...

private:

std::vector<GameObject> Objects;

GameObjects Objects;

};We also need to update Render(), Tick(), and HandleEvent() to handle each object now being a GameObjectPtr (which is an alias for std::unique_ptr<GameObject>) rather than a simple GameObject:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

// ...

void HandleEvent(SDL_Event& E) {

for (GameObjectPtr& Object : Objects) {

Object->HandleEvent(E);

}

}

void Tick(float DeltaTime) {

for (GameObjectPtr& Object : Objects) {

Object->Tick(DeltaTime);

}

}

void Render(SDL_Surface* Surface) {

for (GameObjectPtr& Object : Objects) {

Object->Render(Surface);

}

}

// ...

};Our HandleCollisions() function will need similar updates:

src/GameObject.cpp

// ...

void GameObject::HandleCollisions() {

isOnGround = false;

// Updating the type from GameObject to GameObjectPtr

for (const GameObjectPtr& O : Scene.GetObjects()) {

// Replacing the & operator with .get()

if (O.get() == this) continue;

SDL_FRect Intersection;

if (Bounds.GetIntersection(

// Replacing the . operator with ->

O->Bounds, &Intersection

)) {

isOnGround = true;

Position.y -= Intersection.h;

Velocity.y = 0;

}

}

}Depending on the state of your code, there may be other updates required to accomodate this switch to using pointers. The changes are typically going to involve the following:

- Updating

.operators to be-> - Converting a

std::unique_ptr<GameObject>to aGameObjectorGameObject&using the*operator:*SomePointer - Converting a

std::unique_ptr<GameObject>to a rawGameObject*using theget()method:SomePointer.get()

Using Polymorphism

Now that we've split our game objects across multiple types, our collision system has more information with which to determine its reaction. Below, we log out the what type of object we collided with, and restricted our previous logic to only be used if we collided with a floor type:

src/GameObject.cpp

// ...

void GameObject::HandleCollisions() {

isOnGround = false;

for (const GameObjectPtr& O : Scene.GetObjects()) {

if (O.get() == this) continue;

SDL_FRect Intersection;

if (Bounds.GetIntersection(

O->Bounds, &Intersection

)) {

std::cout << "I hit a " << O->GetTypeName();

if (O->HasType(GameObjectType::Floor)) {

std::cout << "\nReacting to floor..."

isOnGround = true;

Position.y -= Intersection.h;

Velocity.y = 0;

}

}

}

}I hit a floor

Reacting to floor...

I hit a floor

Reacting to floor...

...Text Replacement Macros

We now have a problem that commonly occurs with polymorphic systems. Our child classes are expected to override some simple inherited functions in a predictable, repeated pattern:

class Projectile : public GameObject {

public:

using GameObject::GameObject;

GameObjectType GetType() override {

return GameObjectType::Projectile;

}

std::string GetTypeName() override {

return "Projectile";

}

};As we covered before, we'd usually want to simplify and standardize the overriding of these methods, so we can provide a macro. It might look something like this:

#define GAME_OBJECT_TYPE(TypeName) \

GameObjectType GetType() override { \

return GameObjectType::TypeName; \

} \

\

std::string GetTypeName() override { \

return #TypeName; \

} \Using this macro in a derived class would look like this:

class Projectile : public GameObject {

public:

using GameObject::GameObject;

GAME_OBJECT_TYPE(Projectile)

};We covered text replacement macros in more detail in our

More Examples

With our system now set up, we can add depth with a similar approach we use for any other polymorphic system.

Below, we add a CanPassThrough() method that determines whether our type is a solid object like the floor or something that objects can move through such as light foliage. This is set to true on the base class, but derived classes can override it:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

virtual bool CanPassThrough() { return true; };

// ...

};

// ...

class Floor : public GameObject {

public:

using GameObject::GameObject;

GAME_OBJECT_TYPE(Floor)

bool CanPassThrough() override { return false; }

};We can also add an OnHit() method to our base class, which subtypes can override to create more complex hit interactions. Below, our Projectile type uses this to inflict damage if it hits a Player:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class GameObject {

public:

virtual void OnHit(GameObject& Target) {}

// ...

};

// ...

class Player : public GameObject {

public:

using GameObject::GameObject;

GAME_OBJECT_TYPE(Player)

void TakeDamage(int Damage) {

Health -= Damage;

}

private:

int Health{100};

};

class Projectile : public GameObject {

public:

using GameObject::GameObject;

GAME_OBJECT_TYPE(Projectile)

void OnHit(GameObject& Target) override {

if (Player* P{dynamic_cast<Player*>(&Target)}) {

P->TakeDamage(10);

}

}

};Integrating these new capabilities with our collision system would look something like this:

src/GameObject.cpp

// ...

void GameObject::HandleCollisions() {

isOnGround = false;

for (const GameObjectPtr& O : Scene.GetObjects()) {

if (O.get() == this) continue;

SDL_FRect Intersection;

if (Bounds.GetIntersection(

O->Bounds, &Intersection

)) {

O->OnHit(*this);

if (O->CanPassThrough()) {

// I can pass through this object - no need

// to change my position or velocity

continue;

}

if (O->HasType(GameObjectType::Floor)) {

isOnGround = true;

Position.y -= Intersection.h;

Velocity.y = 0;

}

}

}

}Complete Code

We've included the complete versions of our GameObject and Scene classes below, containing all the techniques and concepts we covered in this lesson.

To keep things simple, we've removed the intersection and relevancy-testing code from the previous lesson:

Files

Summary

In this lesson, we made our game objects interact by implementing a collision system. We replaced arbitrary position limits with detection logic based on bounding box intersections.

We focused on resolving collisions by correcting object positions and velocities, particularly for floor interactions, and applied polymorphism to allow varied responses depending on what objects are colliding.

- Check for collisions by iterating through scene objects and testing bounding box intersections, skipping self-collision checks.

- The intersection rectangle (

SDL_FRect) provides data (width, height) useful for resolving the collision. - Basic floor collision response involves moving the object up by the intersection height and zeroing vertical velocity.

- Use flags like

isOnGroundto communicate collision state to other parts of the game logic (e.g., jumping). - More advanced resolution considers collision angle/sides by comparing intersection width and height or object velocities.

- Object-oriented design with

virtualmethods enables defining specific behaviors (like damage on hit or pass-through ability) for different object types. - Using smart pointers like

std::unique_ptrmanages memory for polymorphic objects stored in collections likestd::vector.

Building with Components

Learn how composition helps build complex objects by combining smaller components