Cameras and View Space

Create camera systems that follow characters, respond to player input, and properly frame your game scenes.

In most games, the player cannot view the entire game world at the same time. Rather, we can imagine the player moving a virtual camera around the world, and what that camera sees determines what appears on the player's screen.

In a top-down game, for example, they might move that camera by clicking and dragging their mouse. In an action game, the camera might be attached to the player character. As such, we need to show the world from the perspective of that camera.

This is another problem that is generally solved by the introduction of another space, commonly called the view space or camera space.

In this lesson, we'll explore how view space works, we'll implement camera movement controls, and create character-following mechanics.

We'll build upon the scene rendering architecture we created in the .

Starting Point

The code below represents the state of our project from the end of the previous lesson. It includes a Vec2 struct for vector math, a Window class for managing the SDL window, an Image class for loading and rendering textures, a GameObject class representing entities in our world, and a Scene class that manages the objects and coordinate transformations.

Files

View Space

Let's add a virtual camera to our Scene class. In the minimalist, two-dimensional case, the only property our camera really needs is its position in world space, so our camera can be represented by a simple Vec2:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

// ...

private:

// ...

Vec2 CameraPosition{0, 0}; // World Space

};Somewhat counterintuitively, to create the illusion of a camera moving through our world, it's more helpful to imagine that the world is instead moving around a stationary camera.

For example, if we wanted to create the illusion of our virtual camera moving to the left, we instead need to move everything in the world to the right:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

// ...

private:

// ...

Vec2 CameraPosition{0, 0}; // World Space

Vec2 ToViewSpace(const Vec2& Pos) const {

return {

Pos.x - CameraPosition.x,

Pos.y - CameraPosition.y

};

}

};Alternative: Vec2 Operators

Our code examples are showing the operations we perform on each component of our position vectors for clarity, but our Vec2 type includes a range of operators that can make our code more succinct.

For example, our ToViewSpace() function can be rewritten (or replaced entirely) with the - operator:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

// ...

private:

// ...

Vec2 ToViewSpace(const Vec2& Pos) const {

// Before

return {

Pos.x - CameraPosition.x,

Pos.y - CameraPosition.y

};

// After

return Pos - CameraPosition;

}

};Using ToViewSpace()

Let's update our transformation pipeline to use our ToViewSpace() function. We need to transform our points from world space to view space based on the camera, and then from view space to screen space based on the viewport properties.

Because we're defining our camera's position in world space, it's important that we perform the view space transformations before we convert our vectors to their screen space representations:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

public:

// ...

Vec2 ToScreenSpace(const Vec2& Pos) const {

// Transform to view space...

auto [x, y]{ToViewSpace(Pos)};

// ...then to screen space

auto [vx, vy, vw, vh]{Viewport};

float HorizontalScaling{vw / WorldSpaceWidth};

float VerticalScaling{vh / WorldSpaceHeight};

return {

vx + x * HorizontalScaling,

vy + (WorldSpaceHeight - y) * VerticalScaling

};

}

// ...

};Camera Movement

Currently, our camera's position is , so our scene should look the same as before:

Let's move our camera to the right and up to confirm our view updates as expected. Given our camera's position is in world space, we move it right by increasing it's x position, and up by increasing it's y position:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

// ...

private:

// ...

Vec2 CameraPosition{300, 50}; // World Space

// ...

};

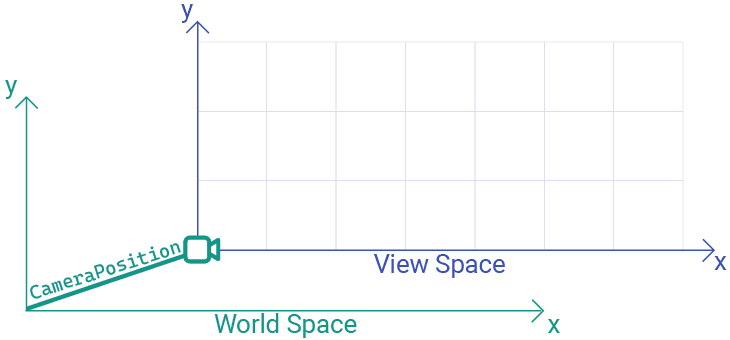

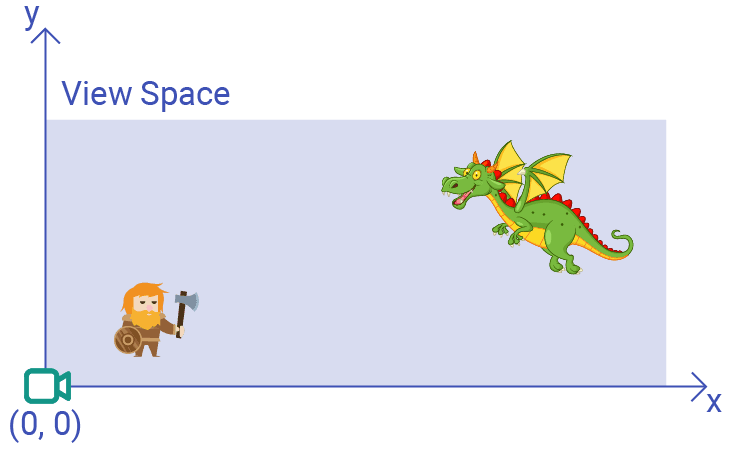

Currently, our view space is defined very similarly to our world space. The only difference is that, in world space, the origin represents the bottom-left of the world whilst, in view space, the origin represents the location of the camera.

We can visualize the difference as the view space being offset from the world space. The direction and magnitude of that offset is controlled by the CameraPosition vector:

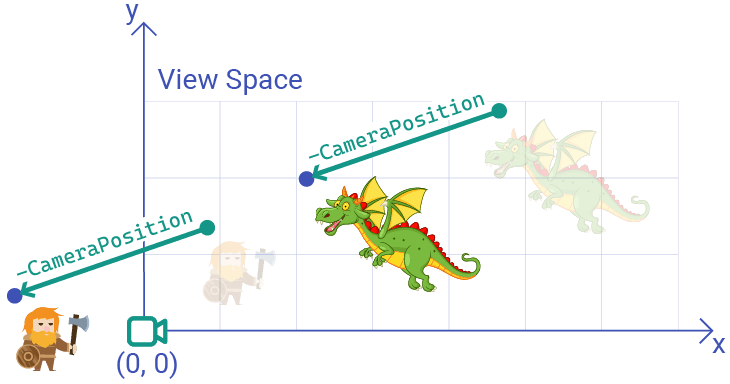

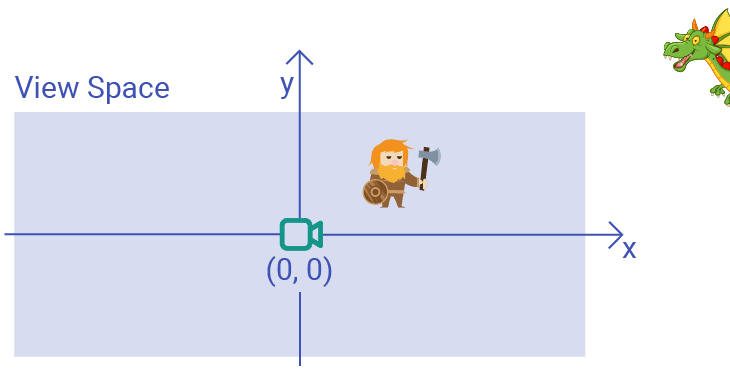

Remember, view space represents the scene as viewed from the perspective of the camera. In view space, the camera doesn't move - it is always at the origin - .

To simulate the effect of a movable camera, we convert world space positions (highlighted in green) to equivalent view space positions (highlighted in blue) by moving them in the opposite direction of the CameraPosition vector.

For example, if our camera moves up and to the right, then from the perspective of the camera, the objects will move down and to the left:

The code in our current ToViewSpace() function implements this:

class Scene {

// ...

private:

Vec2 CameraPosition{0, 0}; // World Space

Vec2 ToViewSpace(const Vec2& Pos) const {

return {

Pos.x - CameraPosition.x,

Pos.y - CameraPosition.y

};

}

// ...

};Field of View

If our CameraPosition is , our world space and view space are identical, so effectively no transformation happens. As such, our scene would look like this:

However, if we imagined a real camera positioned at in our world, this is not exactly what we'd expect the camera to see. We currently have the view space defined as below, where the origin is indeed the location of the camera, but the camera can only see things to its top right:

Instead, we want the camera to sees things "in front" of it. We can represent this as a rectangle positioned such that the camera is in the center of it. Or, equivalently, a view space where the origin represents the center:

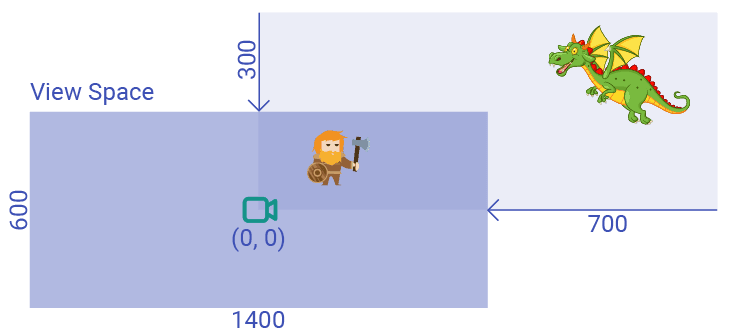

The size of this rectangle is determined by the camera's field of view. For now, we'll keep things simple and make our field of view the same size as our world space - a 1400 x 600 rectangle.

To transform our objects from world space to the definition of view space that includes the origin change, our ToViewSpace() function needs to be slightly expanded. Visually, we can imagine one way of achieving our goal would be moving our camera down and to the left by half of our rectangle's height and width:

But again, our camera doesn't really move in view space - it's position is always . So instead, we replicate the effect by moving our objects by the same amount but in the opposite direction - up and to the right.

In view space, we move objects right by increasing their x position, and up by increasing their y position:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

// ...

private:

Vec2 ToViewSpace(const Vec2& Pos) const {

return {

(Pos.x - CameraPosition.x) + WorldSpaceWidth / 2,

(Pos.y - CameraPosition.y) + WorldSpaceHeight / 2

};

}

// ...

};We should now see the view we'd expect from a camera positioned at in the world space:

We can reposition our camera to the center of the world space to get our original perspective back, but now calculated using a fully implemented view space transformation:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

// ...

private:

// ...

float WorldSpaceWidth{1400};

float WorldSpaceHeight{600};

Vec2 CameraPosition{

WorldSpaceWidth / 2, WorldSpaceHeight / 2

};

};

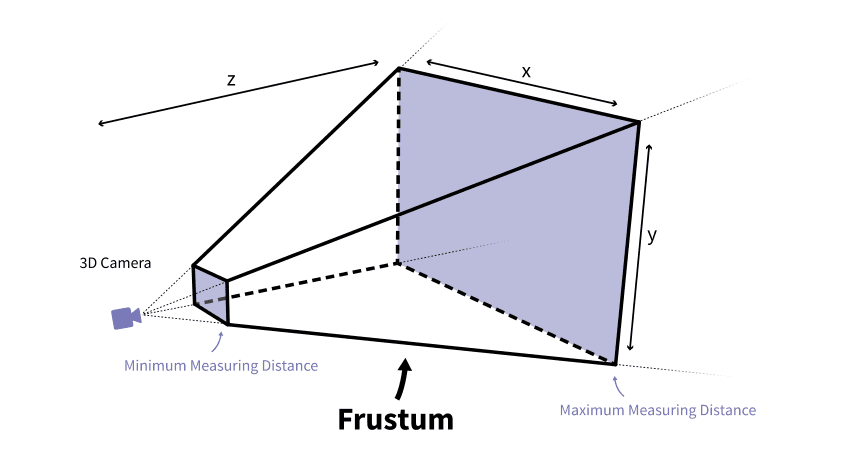

Advanced: Orthographic and Perspective Projection

This example of representing the camera's field of view as a simple rectangle is called an orthographic projection. It is commonly used in 2D scenes as, by their nature, our scenes have no depth. Depth would be a third dimension and, in 3D scenes, it is typically labelled .

In 3D scenes, creating a realistic camera is more complex. The third dimension means we have more complex movement and rotations to model, but depth itself adds complexity. Depth creates the illusion that objects, and the spaces between objects, appear smaller the further away they are from the camera.

Creating this effect involves the field of view being modeled as a frustum - a volume that grows in size as the distance from the camera increases:

Image Source: Jakob Killian

The process of mapping the objects in this three-dimensional view space to a two-dimensional space, such as screen space, is called perspective projection.

Player-Controlled Camera

Let's update our scene to give players control of the camera. Our scene is already receiving events through it's HandleEvent() functions. We can examine the events flowing through our scene to detect if the player has pressed one of their arrow keys.

If they have, we can update our camera's position. Remember, our camera and other objects are now positioned in world space, meaning increasing y now corresponds to moving up:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

public:

// ...

void HandleEvent(SDL_Event& E) {

if (E.type == SDL_EVENT_KEY_DOWN) {

switch (E.key.key) {

case SDLK_LEFT:

CameraPosition.x -= 20;

break;

case SDLK_RIGHT:

CameraPosition.x += 20;

break;

case SDLK_UP:

CameraPosition.y += 20;

break;

case SDLK_DOWN:

CameraPosition.y -= 20;

break;

}

}

for (GameObject& Object : Objects) {

Object.HandleEvent(E);

}

}

// ...

};Attached Cameras

In many games, the camera is attached to some other object in the scene, often the character that the player is controlling. We can replicate this in a few ways. The most direct is to simply examine the player character's position, and set the camera's position accordingly.

CameraPosition = Player.Position;In cases like this, we should be mindful of when our objects are being updated in each iteration of our game loop. To prevent our camera lagging one frame behind the player, we should set the camera's position after the player's position has been updated for the next frame, but before we start rendering that frame.

In our case, our player can't move yet, but a good time in general to perform the update would be after our player-controlled character ticks, but before the scene renders. We'll assume the GameObject that the player is controlling is the first in the scene's Objects array:

Files

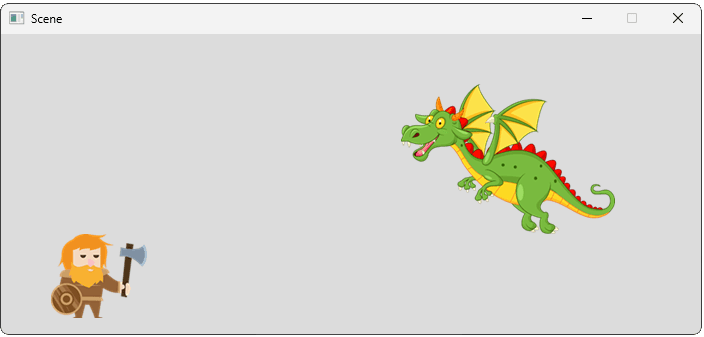

Our camera should now center its view on the player character. Remember that the player's Position denotes the top-left corner of their image, so our object's rendered appearance will appear slightly lower and to the right of their actual Position:

Let's update our HandleEvent() so that arrow keys move the player instead of the camera:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

public:

// ...

void HandleEvent(SDL_Event& E) {

if (E.type == SDL_EVENT_KEY_DOWN) {

switch (E.key.key) {

case SDLK_LEFT:

Objects[0].Position.x -= 20;

break;

case SDLK_RIGHT:

Objects[0].Position.x += 20;

break;

case SDLK_UP:

Objects[0].Position.y += 20;

break;

case SDLK_DOWN:

Objects[0].Position.y -= 20;

break;

}

}

// ...

}

// ...

};The player can now move their character around the scene. And, because the camera is attached to the player's character, the camera will indirectly move too:

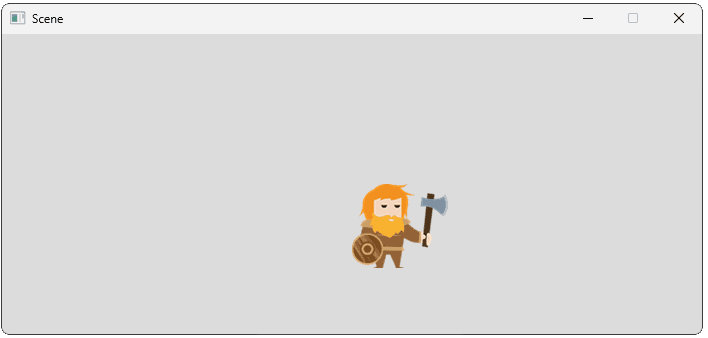

Typically, we don't want the camera to match the character's position exactly. Most games want to apply some offset to the positioning, such that the scene is framed in a way that looks better.

Below, our camera still follows the player character, but is positioned 600 units to the right, and 100 units higher:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

public:

// ...

void Render(SDL_Surface* Surface) {

CameraPosition = Objects[0].Position

+ Vec2{600, 100};

SDL_GetSurfaceClipRect(Surface, &Viewport);

for (GameObject& Object : Objects) {

Object.Render(Surface);

}

}

// ...

};This returns us to our original composition, where our dwarf is currently positioned at , and our camera is attached to the dwarf but with a offset. Adding these, we get a final camera position of , which is at centre of our simple world:

Complete Code

Our updated Scene and GameObject classes are available below:

Files

Additional Spaces

We've walked through a basic world space view space screen space example in these lessons, but larger projects typically include some additional spaces. These spaces are configured to solve specific problems in a complex pipeline. Three common examples are below:

Local Space

Alternative names for this include model space or object space. It is the coordinate system relative to a single object. For example, when an artist is creating a 3D model, that is done in a software package where the model is the only thing in the scene. This means the model's vertices are positioned relative to an origin that typically near center of the model.

When a level designer takes that model and positions it in the overall world, we need a mechanism to move the vertices of the model into that new position. To handle this, each model in the world gets its own transformation process to convert those local space coordinates to world space coordinates based on the model's position, scale, and rotation in the larger world.

Clip Space

Additional spaces are often added between the view space and screen space steps. Clip Space is the result of applying a projection (like the orthographic projection we simulated) to the view space.

In this space, geometry that falls outside the viewing volume (frustum) is "clipped" (discarded or trimmed) because it won't be visible on the screen. This serves as an optimization step in the pipeline to ensure we're not processing geometry that can't possibly be visible to the camera.

Normalized Device Coordinates (NDC)

After clip space, coordinates are typically converted into normalized device coordinates (NDC). This is a standardized coordinate system where the visible part of the screen maps to a specific range, typically from to on the and axes.

This creates an environment that is very similar to screen space, but independent of the actual screen resolution. This standardization simplifies any work we need to do right before displaying the final image. For example, we know the point at in NDC is always the center of the screen, and is always a corner, regardless of the final viewport size.

The final transformation in the pipeline simply maps this normalized range to the actual pixel coordinates of the player's window (screen space).

Summary

In this lesson, we've explored the techniques involved in creating a 2D camera system that can be controlled directly or attached to a game character. Key takeaways:

- Camera systems use coordinate space transformations to create the illusion of movement through the game world.

- Converting between world space and view space requires understanding the camera's position and field of view.

- In 2D games, cameras typically use orthographic projections which represent a simple rectangular view.

- Camera positioning can be manually controlled or automatically attached to follow characters.

- Applying offsets to attached cameras allows for better visual composition of game scenes.

- Coordinate transformations should happen in the correct order: world space view space screen space.

In the next lesson, we'll move away from manual calculations and see how linear algebra can generalize and simplify these transformations.

Matrix Transformations and Homogeneous Coordinates

Learn to implement coordinate space conversions in C++ using matrices and homogeneous coordinates.