Understanding Screen & World Space

Learn to implement coordinate space conversions in C++ to position game objects correctly on screen.

This lesson marks the beginning of the final chapter of our course. Throughout this chapter, we'll cover some fundamental concepts that underpin game engines, computer graphics, and real-time simulation.

This will primarily be useful for those who want to continue learning game engine architecture and real time rendering. The main goal of this chapter is to bridge what we covered in this course to the more advanced implementations that are used in those contexts.

In this lesson, we are looking at spaces. Up until now, we've mostly worked in a single coordinate system where (0,0) is the top-left of the window and units are pixels. This is known as screen space.

However, complex games typically work across multiple spaces. For example, we create our environments and levels in a coordinate system known as world space. This decoupling allows us to create worlds that aren't limited by the window size or screen resolution.

We'll learn how to define these spaces and how to mathematically transform positions from one to the other. We'll initially do this using standard C++ code but, later in the chapter, we'll learn how this process can be unified by the math of matrix multiplication, and the benefits of using this approach.

Screen Space

In all of our projects so far, we've been working within a single coordinate system. We have been creating and managing our objects in screen space - the coordinate system we use to position objects on the player's screen.

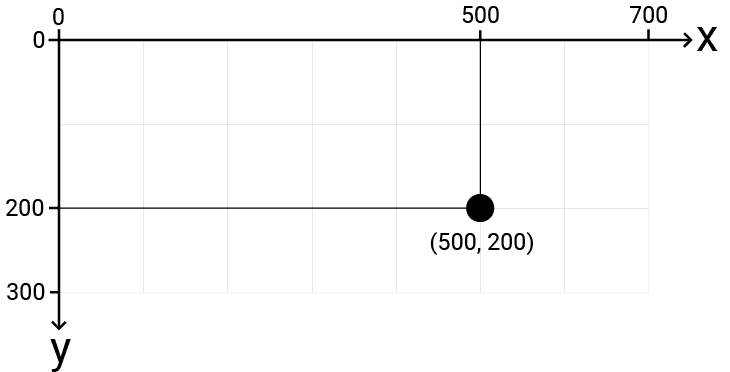

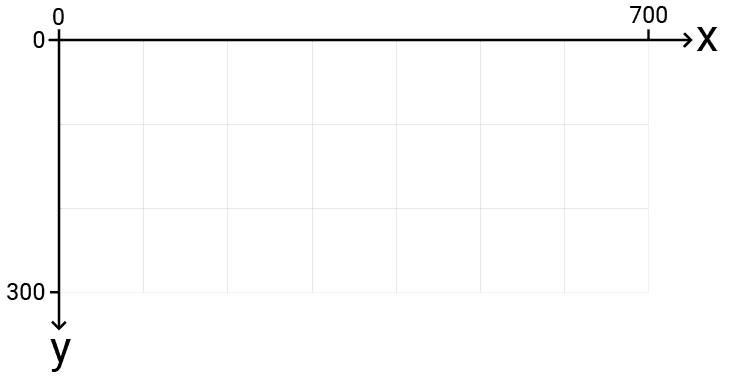

Our screen has been represented using the SDL_Surface associated with the SDL_Window where our game runs. This surface configures the space such that the top-left corner is the origin, with increasing x values moving right and increasing y values moving down.

The space looks like this, with an example position highlighted:

When we start building more complex projects, this approach of programming everything in screen space introduces problems:

- We don't necessarily know the dimensions of the screen space when writing our code. Users may resize the window, or if running in full screen, the resolution might vary.

- We'd like to have the flexibility to define our spaces in a way that makes the problem we're trying to solve as easy as possible. For example, to solve the problem of a realistic physics simulation, we'd prefer to be working in a space based on real world units, such as meters rather than pixels.

- We'd also like the flexibility to redefine the coordinate system of that space. For example, we typically intuitively think of "up" as increasing Y values, but the SDL window's coordinate system works the opposite way. We can set up our world space to work exactly how we want

- What is currently on the screen does not necessarily correspond to everything in our world. A character might only see a small part of the level at any time, but the rest of the world still exists.

Aside from screen space, the next most common system we typically add to our workflow is a world space. This is where objects in world can continue to exist and be updated, even if they're not currently being rendered.

World Space

Most of our positioning and simulation should be done within a coordinate system called the world space. When we create our game levels and worlds, the objects we position within them are defined in this space.

We're free to set this space up in whatever way is most convenient. In 2D games, our world space typically uses an x dimension where increasing values correspond to moving right, and a y coordinate where increasing values correspond to moving up.

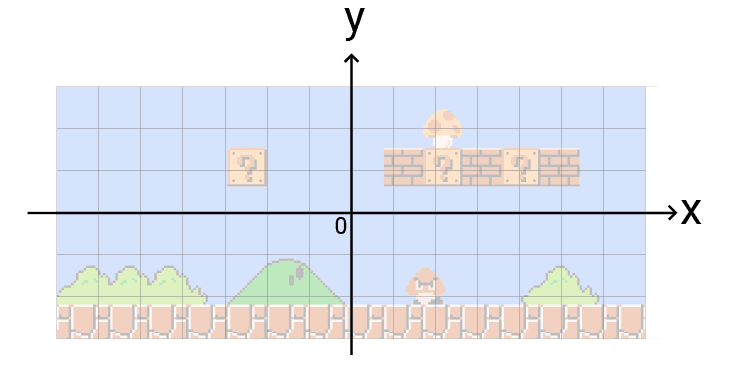

We also need to choose where the origin is. A popular choice is to set up our space such that the origin represents the center of the world:

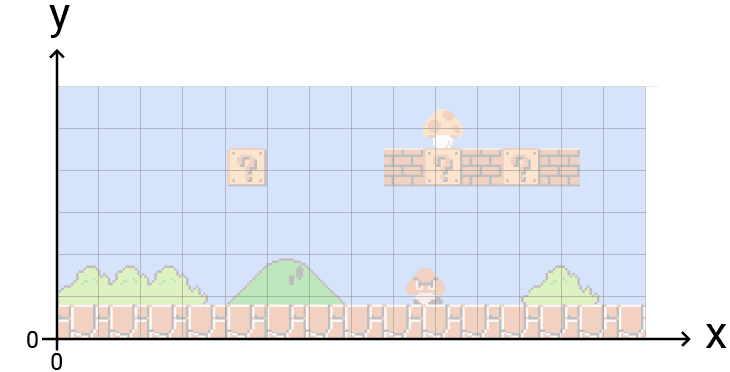

Alternatively, we could define the origin such that x = 0 aligns with the left edge of our level and y = 0 aligns with the bottom edge:

This avoids negative numbers for positions within the level boundaries, which can sometimes simplify logic.

Transformations

Even though our objects are positioned in world space, the goal is to render them onto the player's screen. We need a way to transform objects from their world space position to the corresponding screen space position.

This is a challenge because our spaces typically have different properties:

- They can use different coordinate systems (e.g., Y-up vs Y-down).

- The origin can represent a different location (e.g., bottom-left vs top-left).

- They can have a different size or scaling factor. Our previous chapter hinted at this when we introduced a

PIXELS_TO_METERSconstant. This represented the scaling factor from world space units (meters) to our screen space units (pixels).

Example World Space and Screen Space

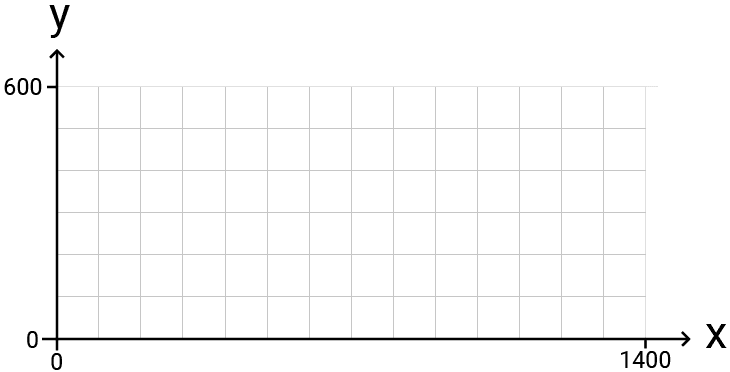

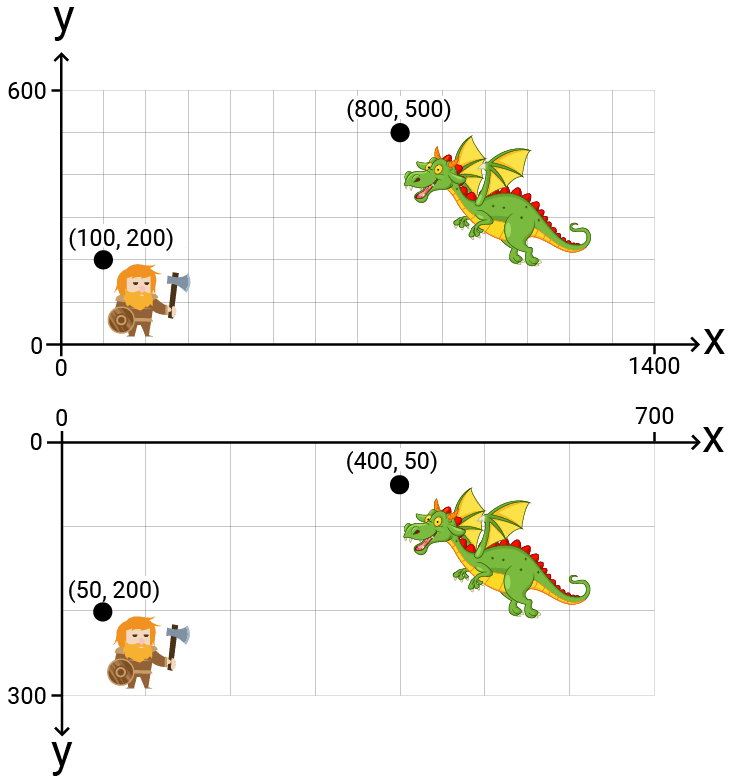

Let's establish a fixed example to work with. We'll imagine our world space looks like this:

The key properties are:

xis horizontal, increasing to the right.yis vertical, increasing up.- Origin is at the bottom-left.

- The world spans from (0, 0) to (1400, 600).

Our screen space is the SDL_Surface of a window:

The key properties are:

xis horizontal, increasing to the right.yis vertical, increasing down.- Origin is at the top-left.

- The window dimensions are 700x300 - half the size of our world space. We'll learn how to make this dynamic later in the chapter, so our conversion can be based on the player's window or screen resolution rather than these hard-coded dimensions.

Transforming World Space to Screen Space

We need to define logic that updates the x and y coordinates of an object in world space to their equivalent values in screen space.

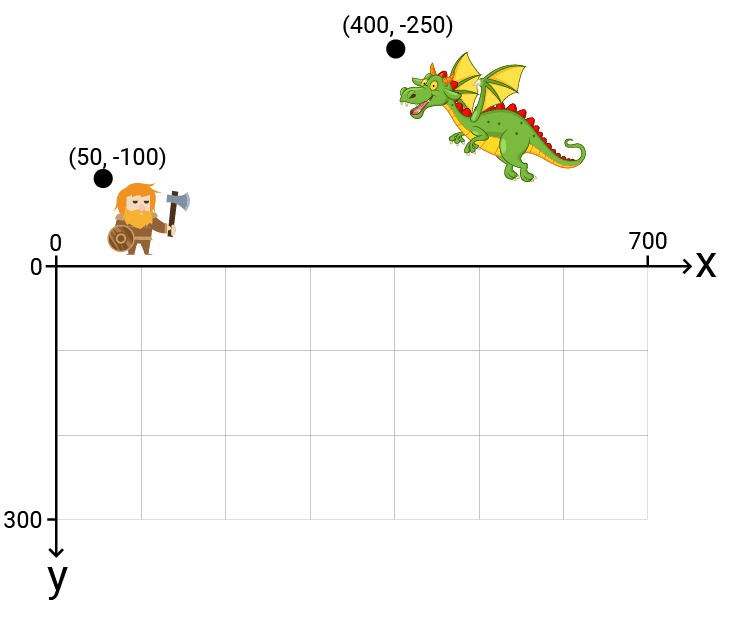

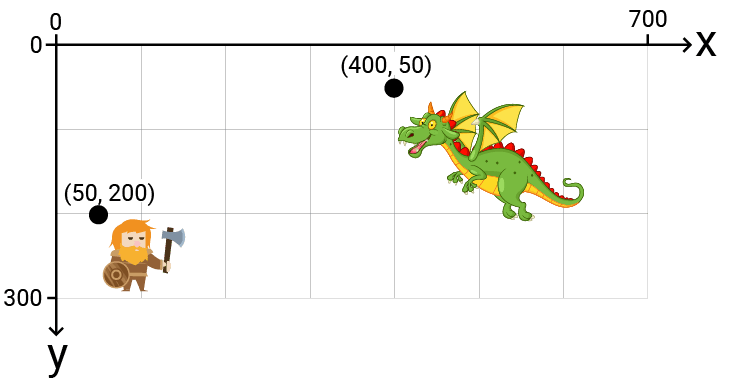

The following diagram shows the start and end point of that process with two example objects - a dwarf and a dragon character:

Based on our example properties, the transformation needs to:

- Account for the different size: Scale vectors down by 50% (screen space is 700x300 vs world space 1400x600).

- Account for the different coordinate system: Invert the

ycoordinates because screen space Y increases downwards. - Account for the different origin: Increase

ycoordinates by 300 (the screen height). Since screen Y increases downwards, adding to Y moves the point down, correctly positioning our bottom-left origin to the bottom of the screen.

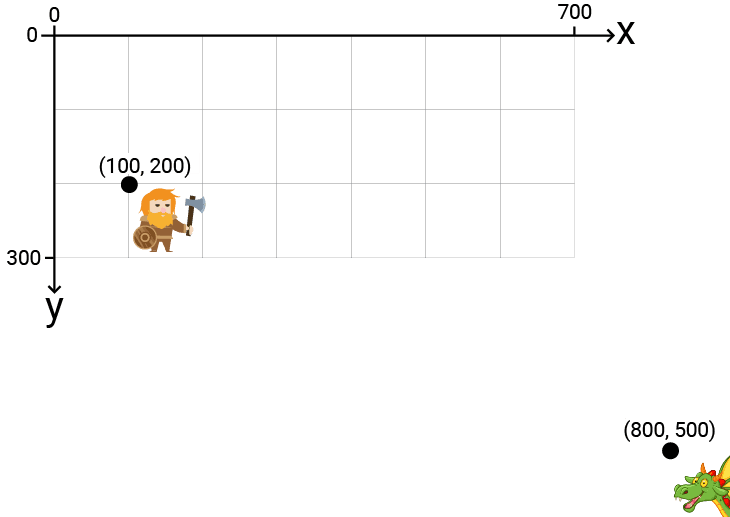

Let's visualize this step-by-step. First, here are our characters in screen space using their raw world coordinates, without transformation:

Step 1: Accounting for the Different Size

Multiplying the position vectors by scales them down, moving them closer to the origin:

Step 2: Accounting for the Different Coordinate System

We negate the vertical position by multiplying by . This flips them across the x-axis:

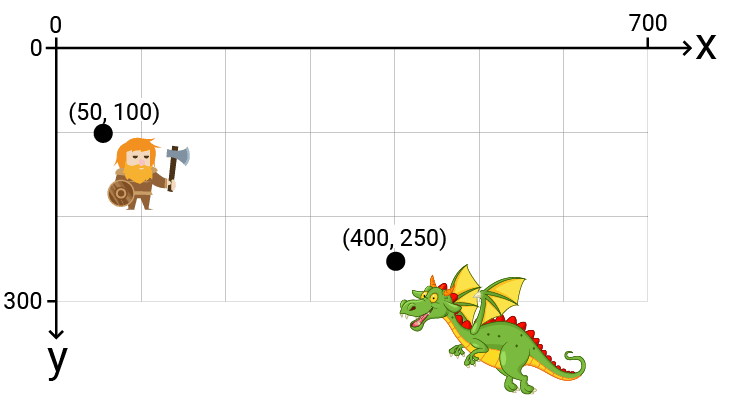

Step 3: Accounting for the Different Origin

Finally, we increase the components by . In screen space, this moves the objects down, placing them in their correct final positions:

Implementing this transformation in code looks like this:

Files

Or, more concisely:

src/main.cpp

// ...

Vec2 ToScreenSpace(const Vec2& Pos) {

return {

Pos.x * 0.5f,

(Pos.y * -0.5f) + 300

};

}

// ...We can test this logic by transforming some known points and verify the output:

src/main.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include "Vec2.h"

Vec2 ToScreenSpace(const Vec2& Pos) {/*...*/}

int main(int, char**) {

// A position in the center of

// the 1400x600 world space...

Vec2 P{700.0, 300.0};

// ...transformed to the center

// of the 700x300 screen space

std::cout << "[700x300 SCREEN SPACE]";

std::cout << "\nCenter: "

<< ToScreenSpace(P);

// Some more positions

std::cout << "\nBottom Left: "

<< ToScreenSpace({0, 0});

std::cout << "\nTop Left: "

<< ToScreenSpace({0, 600});

std::cout << "\nBottom Right: "

<< ToScreenSpace({1400, 0});

std::cout << "\nTop Right: "

<< ToScreenSpace({1400, 600});

return 0;

}[700x300 SCREEN SPACE]

Center: { x = 350, y = 150 }

Bottom Left: { x = 0, y = 300 }

Top Left: { x = 0, y = 0 }

Bottom Right: { x = 700, y = 300 }

Top Right: { x = 700, y = 0 }Summary

In this lesson, we introduced the concept of spaces and how they differ. To render a game world onto a screen, we must mathematically transform positions from one coordinate system to another.

Key takeaways:

- Screen Space uses pixel coordinates with the origin at the top-left (Y increases down).

- World Space uses our choice of convenient units (like meters) with a chosen origin, often bottom-left or center (Y increases up).

- Transforming between spaces involves accounting for differences in scale, axis orientation, and origin position.

- We can implement transformations as simple mathematical functions.

In the next lessons, we'll remove this hardcoded 700x300 restriction, and learn how to make this transformation support any window or viewport size.

Scene Rendering

Create a scene management system that converts world space coordinates to screen space for 2D games.