Scene Rendering

Create a scene management system that converts world space coordinates to screen space for 2D games.

When developing games, we need a way to represent our virtual world and then transform it to display on a screen.

In this lesson, we'll create a complete scene system that lets us position game objects using world coordinates, and then automatically converts those positions to screen coordinates when rendering.

If you want to follow along, a basic starting point that uses simplified versions of techniques we covered previously is provided below:

Files

Rendering Scenes

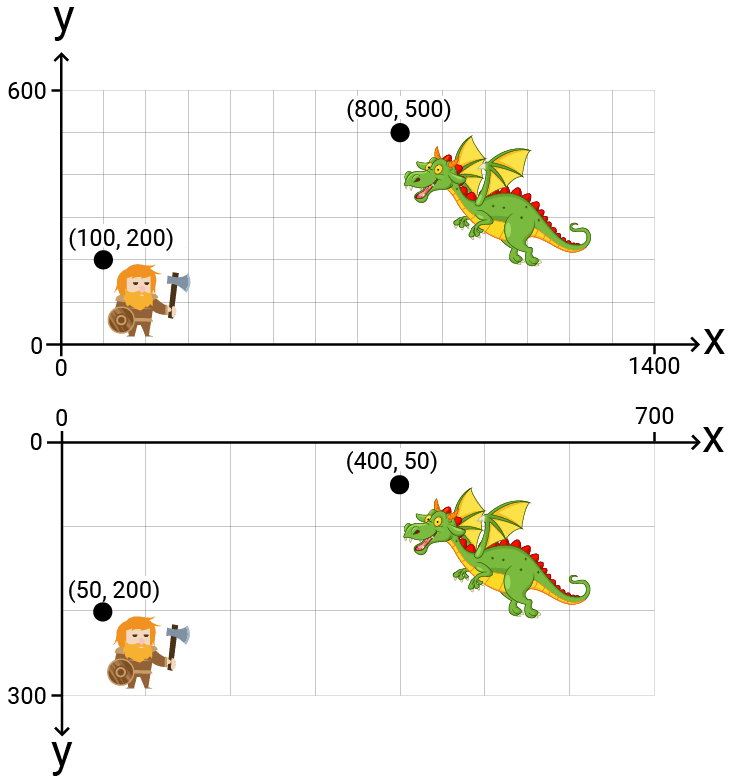

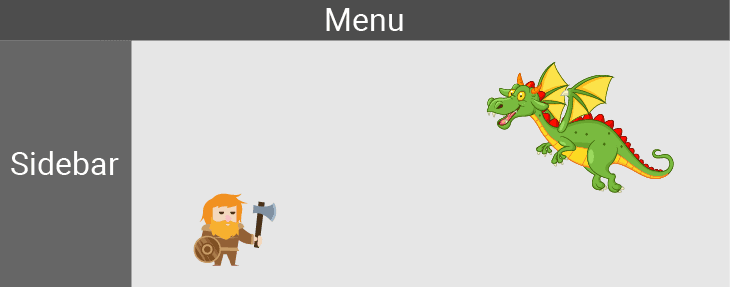

In the previous lesson, we worked with the example scene illustrated below. The top shows the positions in world space, with the bottom showing the corresponding positions in screen space:

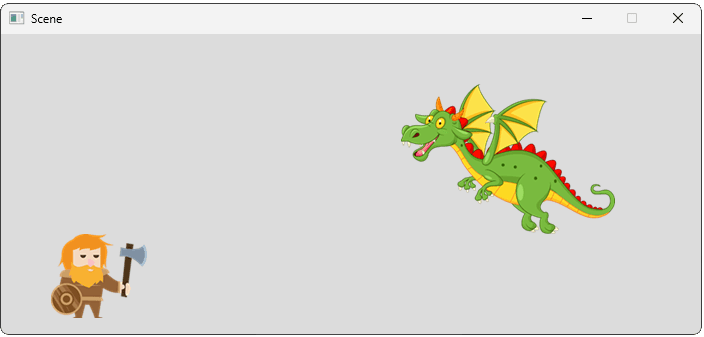

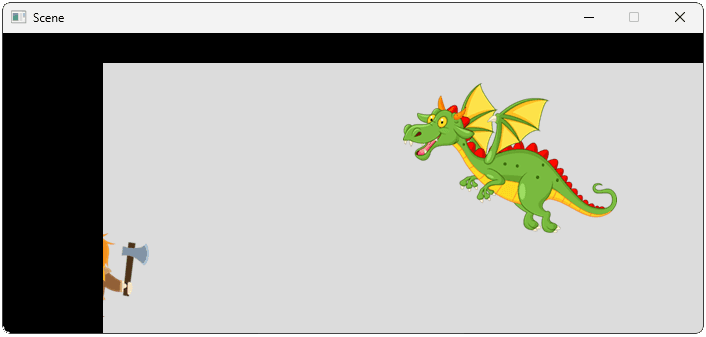

Let's add the two objects to our scene. As a quick test, we'll initially set their positions directly in screen space to confirm everything we've done so far works:

src/Scene.h

// ...

#include <string>

class Scene {

public:

Scene() {

std::string Base{SDL_GetBasePath()};

Base += "Assets/";

Objects.emplace_back(

Base + "dwarf.png",

Vec2{50, 200}

);

Objects.emplace_back(

Base + "dragon.png",

Vec2{400, 50}

);

}

// ...

};

Working in World Space

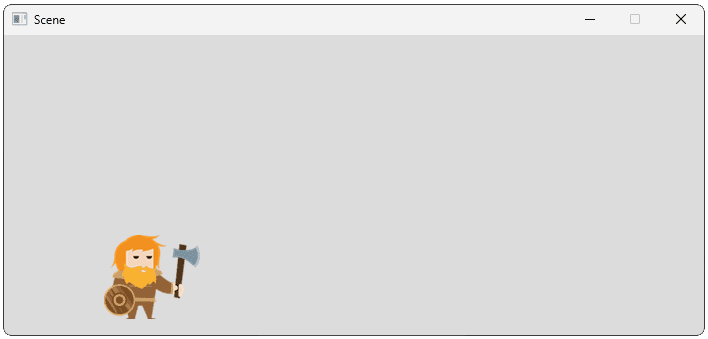

This looks good, however, we want to work in world space, not screen space. Let's update the positions of the objects in our scene to their world space coordinates:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

public:

Scene() {

std::string Base{SDL_GetBasePath()};

Base += "Assets/";

Objects.emplace_back(

Base + "dwarf.png",

Vec2{100, 200}

);

Objects.emplace_back(

Base + "dragon.png",

Vec2{800, 500}

);

}

// ...

};

This looks less good, so we need to implement the world space to screen space transformation we designed in the previous lesson.

As with anything in programming, there are countless ways we can set this up. We can scale our implementation up as our needs get more complex, but it's best to keep things as simple as possible for as long as possible.

A simple implementation might involve adding the transformation logic to our Scene object. For now, we'll assume our screen space and world space are the same as the example we worked through in the previous lesson. As such, we'll use the same transformation function we created in that lesson:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

public:

// ...

Vec2 ToScreenSpace(const Vec2& Pos) const {

return {

Pos.x * 0.5f,

(Pos.y * -0.5f) + 300

};

}

// ...

};For our objects to access this function, we need to provide them with a reference to the Scene they're part of. We can do that through the constructor and save it as a member variable, or pass it to each Render() invocation. We'll go with the constructor approach and have our Scene pass a reference to itself using the this pointer:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

public:

Scene() {

std::string Base{SDL_GetBasePath()};

Base += "Assets/";

Objects.emplace_back(

Base + "dwarf.png",

Vec2{100, 200},

*this

);

Objects.emplace_back(

Base + "dragon.png",

Vec2{800, 500},

*this

);

}

// ...

};Let's update our GameObject constructor to accept this Scene reference. However, because our Scene.h header is already including GameObject.h, we should be cautious with having GameObject.h also include Scene.h. This would result in a circular dependency.

Instead, within GameObject.h, we can forward-declare the Scene class:

src/GameObject.h

// ...

class Scene;

class GameObject {

public:

GameObject(

const std::string& ImagePath,

const Vec2& InitialPosition,

const Scene& ParentScene

) : Image{ImagePath},

Position{InitialPosition},

ParentScene{ParentScene} {}

// ...

private:

Vec2 Position;

Image Image;

const Scene& ParentScene;

};Finally, let's update our Render() function to ensure our world space Position variable is converted to screen space for rendering.

That .cpp file can #include the Scene definition, meaning we can send our Position vector through the ToScreenSpace() transformation function:

src/GameObject.cpp

#include <SDL3/SDL.h>

#include "GameObject.h"

#include "Scene.h"

#define DRAW_DEBUG_HELPERS

void GameObject::Render(SDL_Surface* Surface) {

Image.Render(

Surface,

ParentScene.ToScreenSpace(Position)

);

#ifdef DRAW_DEBUG_HELPERS

auto [x, y]{ParentScene.ToScreenSpace(Position)};

SDL_Rect PositionIndicator{

int(x) - 10, int(y) - 10, 20, 20

};

const auto* Fmt{SDL_GetPixelFormatDetails(

Surface->format

)};

SDL_FillSurfaceRect(

Surface, &PositionIndicator,

SDL_MapRGB(Fmt, nullptr, 220, 0, 0)

);

#endif

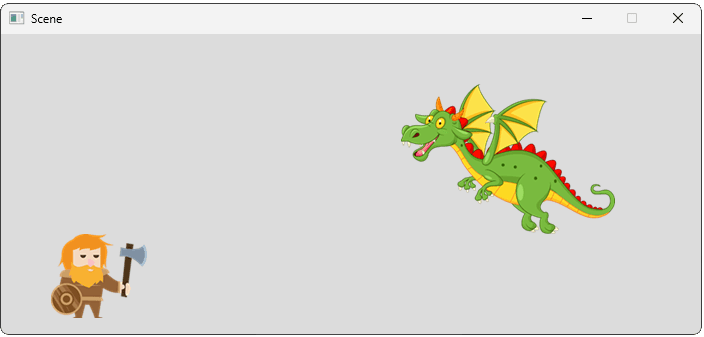

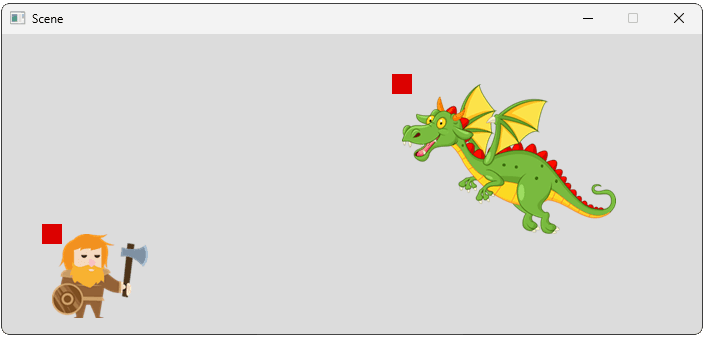

}Running our game, we should see the viewport transformation rendering objects in the correct position:

We now have an entirely different space to work with in our scene. When we implement some new capability to our game, we can now decide whether using world space or screen space is more convenient for that feature.

We can also configure our world space in whatever way we prefer.

Viewports and Clip Rectangles

So far, our program's rendering pipeline has assumed its output is covering the entire area of our window, but that's not necessarily the case. In a more complicated application, our rendering pipeline may only have access to a small portion of the available area. Other parts of the screen, such as UI elements, may be controlled by other parts of our program.

From the perspective of a renderer, the area of the screen it is rendering to is typically called it's viewport. For a renderer to transform its content correctly, it needs to be aware of this viewport's size, and where it is positioned on the screen.

In our examples, our rendering has involved performing blitting operations onto an SDL_Surface, typically the SDL_Surface associated with an SDL_Window. The area of an SDL surface that is available for blitting is called the clipping rectangle.

SDL_GetSurfaceClipRect()

To get the clip rectangle of a surface, we create an SDL_Rect to receive that data. We then call SDL_GetSurfaceClipRect(), passing a pointer to the surface we want to query, and a pointer to the SDL_Rect that the function will update:

SDL_Rect ClipRect;

SDL_GetSurfaceClipRect(

SomeSurfacePointer,

&ClipRect

);By default, the clipping rectangle is the entire surface. Let's find out what the clipping rectangle is of our window's surface:

src/Window.h

#pragma once

#include <iostream>

#include <SDL3/SDL.h>

class Window {

public:

Window() {

SDLWindow = SDL_CreateWindow(

"Scene",

700, 300, 0

);

SDL_Rect ClipRect;

SDL_GetSurfaceClipRect(

SDL_GetWindowSurface(SDLWindow),

&ClipRect

);

std::cout << "x = " << ClipRect.x

<< ", y = " << ClipRect.y

<< ", w = " << ClipRect.w

<< ", h = " << ClipRect.h;

}

// ...

};x = 0, y = 0, w = 700, h = 300This is not surprising, as we've noticed that our objects can render their content to any part of the window's surface. However, this clipping rectangle can be changed to only cover a part of the surface.

SDL_SetSurfaceClipRect()

To change a surface's clipping rectangle, we call SDL_SetSurfaceClipRect(), passing a pointer to the SDL_Surface, and a pointer to an SDL_Rect representing what we want the new rectangle to be.

Below, we update the clipping rectangle so only the bottom-right of our window is available for rendering:

src/Window.h

#pragma once

#include <iostream>

#include <SDL3/SDL.h>

class Window {

public:

Window() {

SDLWindow = SDL_CreateWindow(

"Scene",

700, 300, 0

);

SDL_Rect ClipRect{100, 30, 600, 270};

SDL_SetSurfaceClipRect(

SDL_GetWindowSurface(SDLWindow),

&ClipRect

);

}

// ...

};This means that future blitting operations cannot overwrite the left 100 columns of pixels, and the top 30 rows:

If we want to set the clip rectangle back to the full area of the surface, we can pass a nullptr to SDL_SetSurfaceClipRect():

SDL_SetSurfaceClipRect(

SDL_GetWindowSurface(Window),

nullptr

);Note that the SDL_Surface associated with an SDL_Window is destroyed and recreated when the window is resized. As such, if our program is applying a clip rectangle to that surface, we need to listen for window resize events and recalculate and reapply our clip rectangle when they happen.

Dynamic Transformations

It is rarely the case that our transformations are fully known at the time we write our code. They usually include variables that are not known at compile time. In the next lesson, we'll implement the most obvious example of this - we'll add a player-controllable camera, which determines which part of our world gets displayed on the screen on any given frame.

Even now, our simple transformation is a little more static than we'd like. It assumes the size of our viewport is exactly 700x300. If we wanted to let the user resize our window, or if we wanted our window to go full screen, we need to make our transformation function a little smarter by supporting dynamic viewport sizes.

Each invocation of our Render() function is being provided with the pointer to the SDL_Surface. We can retrieve the clip rectangle associated with that surface, and use it to update a member variable in our Scene:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

// ...

private:

// ...

SDL_Rect Viewport;

};Note that, because this Viewport value is eventually going to control how objects in our scene are to be transformed to view space, it's important that we update it before we render those objects:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

public:

// ...

void Render(SDL_Surface* Surface) {

SDL_GetSurfaceClipRect(Surface, &Viewport);

for (GameObject& Object : Objects) {

Object.Render(Surface);

}

}

// ...

};We'll now update our ToScreenSpace() transformation to no longer assume we need to transform positions to a 700x300 space. Instead, we'll calculate the values dynamically based on our viewport size:

src/Scene.h

// ...

class Scene {

public:

// Before:

Vec2 ToScreenSpace(const Vec2& Pos) const {

return {

Pos.x * 0.5f,

(Pos.y * -0.5f) + 300

};

}

// After:

Vec2 ToScreenSpace(const Vec2& Pos) const {

auto[vx, vy, vw, vh]{Viewport};

float HorizontalScaling{vw / WorldSpaceWidth};

float VerticalScaling{vh / WorldSpaceHeight};

return {

vx + Pos.x * HorizontalScaling,

vy + (WorldSpaceHeight - Pos.y) * VerticalScaling

};

}

private:

float WorldSpaceWidth{1400};

float WorldSpaceHeight{600};

// ...

};Now, our transformation only assumes that our world space spans from (0, 0) to (1400, 600) and that, compared screen space, the axis is inverted. These are valid assumptions, as these characteristics are known at compile-time, and they do not change at run-time.

To test our new transformation function, we can make our window resizable using the SDL_SetWindowResizable() function:

src/Window.h

// ...

class Window {

public:

Window() {

SDLWindow = SDL_CreateWindow(

"Scene",

700, 300, 0

);

// Update an existing window to be resizable

SDL_SetWindowResizable(SDLWindow, true);

// ...

}

// ...If we did everything correctly, our position vectors (represented by the red squares) should now maintain their relative positioning, respecting both the window size and the clip rectangle of the surface they're rendering to:

Transformations in Complex Games

In the basic objects we're managing in this chapter, the transformation from world space to screen space is only being applied to a single point on each object. This Position vector defines where the top-left corner of where our Image will be rendered.

In this course, those images are stored as SDL_Surface objects. Those image surfaces already use the same coordinate system as the SDL_Window surface representing our screen space, so their individual pixels do not need to be transformed.

If we wish, we could expand our GameObject class with additional position data - for example, the location of the bottom-right corner of the image. We could then send this variable through our transformation function, and use the result to control the scaling of our image.

In a more complex games, particularly 3D games, an object can have thousands or even millions of positions defined in world space. Most notably, those are the positions of the vertices used to represent the three-dimensional shape of that object:

Image Source: ACM SIGARCH

Because of this, there are significantly more transformations required in a typical 3D game, but the idea is fundamentally the same. We just have many more points to transform and, in the case of a 3D game, each point has a third component to represent its position in that third dimension.

Complete Code

Complete versions of our updated Scene, Window, and GameObject classes are below:

Files

Summary

In this lesson, we've implemented a scene management system that bridges the gap between world space (where our game logic lives) and screen space (where rendering happens).

Our system automatically transforms coordinates between these spaces and adapts to changing viewport dimensions. Key takeaways:

- Transformation functions convert world coordinates to screen space for rendering

- Dynamic viewport handling ensures our scene renders correctly at any window size

- Clip rectangles control which parts of the window surface are available for rendering

Cameras and View Space

Create camera systems that follow characters, respond to player input, and properly frame your game scenes.